A couple of months ago, I decided to rewatch Padayappa for the first time in quite some time. This was Superstar Rajinikanth at the most electrifying stage of his career, coming off fantastic genre-defining films like Annamalai and Baasha. As a whole, Padayappa is still as entertaining as it was 20 years ago. But I also noticed something about the film, something that made me cringe, something that I hadn’t paid much attention to watching it as a kid nor a teenager: Padayappa, both the film and the character is terribly misogynistic. This is of course highlighted in the scene — a scene mind you, that’s designed to garner claps and cheers — where Padayappa (Rajinikanth) lectures Neelambari (Ramya Krishnan) on how to be a “proper” woman.

He goes something like…

“A woman should have patience; she shouldn’t get angry.

She should show humility and be submissive; not be hasty.

She should be disciplined and calm; shouldn’t be yelling.”

And then he concludes by saying: “Most importantly, a woman should learn how to behave like a woman.”

It is at this point, where I hid my face in the palm of my hands. Padayappa is a film that presents the educated, confident, outspoken woman as a lustful, vengeful and envious villain while the uneducated, head-bowing, reserved, timid one is presented as the “ideal” lady. This conservative idea of a “proper” woman has been a part of Tamil film pop culture since the early days of black and white films.

That said, over the past couple of years, there appears to be a slight paradigm shift in the way women characters are being written in Tamil cinema. Just compare the women in Kaala to that of Sivaji: The Boss. Not to mention the plethora of Nayanthara and Jyothika movies that have come out in recent months. But films like Raatchasi and Imaikka Nodigal, in which the women are written as educated and highly capable, don’t necessarily push the envelope or shatter the glass ceiling as far as ways in which a female character can be portrayed (at least by global cinema standards).

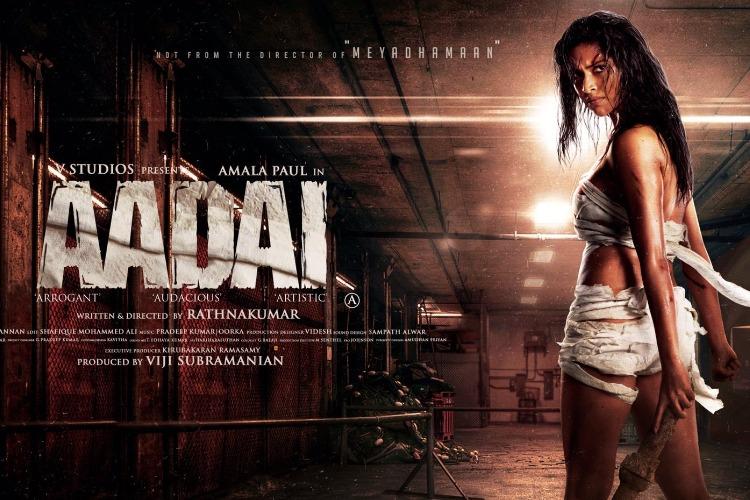

Which brings us to Aadai, a small budget survival-thriller starring Amala Paul.

Here, our female lead is brazen, outspoken, educated, dresses however she pleases, rides a sports bike, occasionally gets drunk with her friends, casually uses the F-bomb, is the lead host of a popular prank show of a major TV Network, doesn’t necessarily believe in god, occasionally smokes a joint and dates the cute guy of her choosing. In other words, she sounds like most of my gal friends. It’s funny how the most interesting Tamil movie female character in recent memory is one who’s simply normal and relatable.

But writer-director Rathna Kumar doesn’t stop there. Kamini, the Amala Paul character, is also slightly obnoxious, thick-skinned and inconsiderate. Her prank show is distasteful and could very much ruin someone’s day badly, at one point, she locks her colleague in the bathroom and steals her TV slot. She’s also a total dick to a guy who just professed his feelings for her and doesn’t call her mom and inform her that she’ll be coming home late.

All of this is wonderfully established in the humorous and gripping first half. (The scene where Kamini, while under the influence of magic mushrooms, starts stripping in front of her friends is uncomfortable to watch and I mean that as a compliment to the director and Amala Paul’s performance.) After a crazy night of drinking and partying, Kamini wakes up in an empty office building. Her clothes, phone and friends are nowhere to be found.

It’s an excellent set up for a survival-thriller that also doubles as a character study. It reminded me a little of 2014’s Wild, in which Reese Witherspoon’s character goes on a thousand-mile hike alone as a way to self actualize. The question is, stripped away of all her clothes and left to fend for herself, what will we learn about Kamini? What will she learn about herself? More importantly, what sort of transformation will she undergo? Who will emerge on the other side?

This to me, felt like a perfect opportunity to tell a human story. Perhaps, after being completely broken down and shattered in the second act, Kamini would be reborn as a more humble and caring individual. Those ideas present as well. The problem is, director Rathna Kumar bookends his film with statements that revolve around feminism.

Aadai opens with a historical story told through stylistically rendered animation. We see lower caste women protesting against a king who has made a law criminalising women who cover their breasts unless an expensive tax is paid. One of the protestors cuts off her breast and commits suicide becoming a martyr in the process. This theme-setting animation tells us that Aadai is going to be a story that thematically revolves around women’s fight against misogyny and the status quo.

Later, during the climactic scene of the film, Kamini finds herself on the receiving end of a lecture from one of her prank show victims. She says a lot including a line that goes something like: “what is wrong with the women of today? Back in the day, women protested to cover up their breasts, these days with campaigns #FreeTheNipple, women are protesting to bare their breasts.” Kamini then realises the “error of her way.”

We have to ask ourselves, what is Rathna Kumar trying to imply with his opening and closing statements? He seems to indicate that there’s a right sort of feminism (women who fight for their rights to cover up) and a wrong sort of feminism (women who wish to free their nipples). This is very apparent in the presentation of Kamini as a character.

When we first meet her, she’s a T-shirt and jeans kinda gal. At one point, her conservative mother scolds her because her bra strap is showing. She tells her mother that it’s no big deal (here, she’s framed as someone who’s unlikable). At the end of the film, she’s dressed in traditional attire (here, she’s framed as a hero — an investigative journalist who goes undercover and catches sexual offenders in the film industry).

This is why Aadai, despite its good intentions, is rather problematic. Rathna Kumar paints ‘Free the Nipple’ as a vulgar antithesis of the women depicted in the opening historical animation. In reality, they’re both two sides of the same coin, fighting against a patriarchal society to achieve similar goals: the reclamation and autonomy of women’s bodies. In both cases, women are basically saying: “dear men, stop telling us how we should or shouldn’t dress.” While Rathna Kumar thinks ‘Free the Nipple’ is about Millenials campaigning for the rights to flaunt their “sexy parts”, the campaign is more about equality and de-sexualizing women’s bodies.

Intentionally or unintentionally, Aadai feels more anti-feminist than feminist. At the end of it, Kamini has changed the way she dresses up and we don’t see her cussing, drinking or smoking. The idea is that she’s now transformed into an ideal woman.

Some of you might be thinking isn’t it good that the protagonist quits smoking? Not quite. The problem isn’t with what Kamini does, but how and why she does it. Let’s compare it to the Karthik Subbaraj directed Rajinikanth film, Petta. There, Rajinikanth tells Vijay Sethupathi that he should stop smoking as it’s bad for health. This statement has got nothing to do with the character’s gender. In Aadai, when Kamini’s mother discovers that she drinks, she breaks down in tears. Words like “dignity” and “shame” are thrown around. Here, “drinking” is tied directly to Kamini’s gender (i.e. a woman who drinks and parties brings shame to her family).

Have a look at the two sentences below.

A: Sandra, you should quit smoking. It’s bad for health.

B: Sandra, women shouldn’t smoke. What would people think?

There’s an important difference between A and B, a difference that is unfortunately absent in Aadai. I’m reminded of the ignorant social media comment sections when the trailer of 90 ML first dropped. A common comment: “How can women behave that way [openly talk about sex, drink and smoke]? Feminist movies should be about women striving to be successful in their careers, etc.”

The general reaction towards the 90ML trailer highlighted people’s general lack of understanding of feminism. Feminism is about equality. Equality in the workforce, equality when it comes to access to education, equality in society, equality period. The basic idea is to eliminate the double standard when it comes to the way men and women are perceived by society.

- Women should be allowed to be CEOs in companies. Just like men, they should be judged based on their capabilities and achievements.

- Women should be allowed to drive. Just like men, they shouldn’t be allowed to if they’re blind.

- Women should be allowed to smoke. Just like men, they should only be criticized for killing themselves and those around them as well as polluting the environment.

- Women should be allowed to drink. Just like men, they should be judged for mistaking alcohol for mineral water.

- Women should be allowed to masturbate. Just like men, they should remember to lock the door and use headphones while watching porn.

- Women should be free to express their sexuality. Just like men, they should remember to use protection.

The list can go on and on and on. The point being, if you’re gonna tell your daughter/sister/wife that she should or shouldn’t do something, ask yourself if you’ll say the same to your son/brother/husband?

So, what could’ve been done differently in Aadai?

I go back to Jean-Marc Vallee’s Wild. Pre-hike, the Reese Witherspoon character was an alcoholic, drug-addict and someone with very little self-respect. At the end of the film, we understand that she’s morphed into someone with self-confidence and self-worth. The transformation is nuanced, subtle but immensely empowering.

Aadai would’ve been a much more powerful film had Kamini still maintained a lot of what made her a regular 20-something-year-old woman. If she still dressed the way she did at the start, still indulged in her vices but is a different individual attitude-wise (i.e. caring, humble, polite). If she still drank but called home to inform her mom first.

The problem with Aadai is that it’s unsure of itself and what it’s trying to say. Instead of having Kamini transform just into a better person, Ratna Kumar also transforms her into his idea of a “proper” woman. It feels like a contradiction to the film’s ballsy and mostly brilliant second act (the actual survival part). We see Kamini vulnerable, we see her dig deep unable to find her usual confidence, we see her run away and hide from a perverted man, we see her as an amazonian warrior (the film’s most brilliant piece of imagery) chasing away a pack of hungry dogs (these dogs symbolise men, who see women as nothing but a piece of meat). But because of its opening and closing statements, Aadai fumbles and falls.

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook or Telegram for more updates and breaking news.