Documentary photographer Mogan Selvakannu didn’t always have it easy. This Mantin bred boy went through a series of jobs before going back to university in his thirties to pursue his passion, documentary photography.

Within his first year in University of South Wales, Cardiff, he was commissioned by the British Broadcasting Corporation. He went on to excel in his course, graduating this July. The photographer was then featured on BBC Creative’s Photography Exhibition.

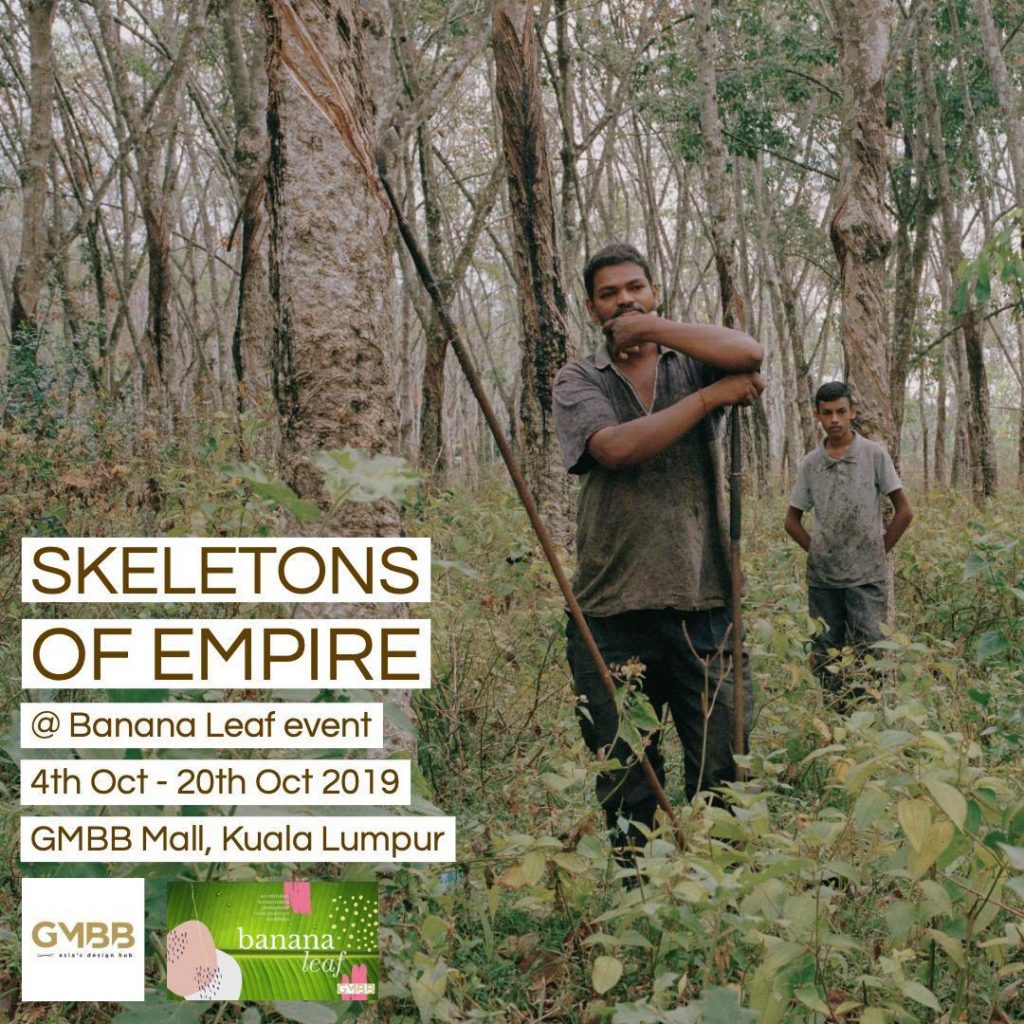

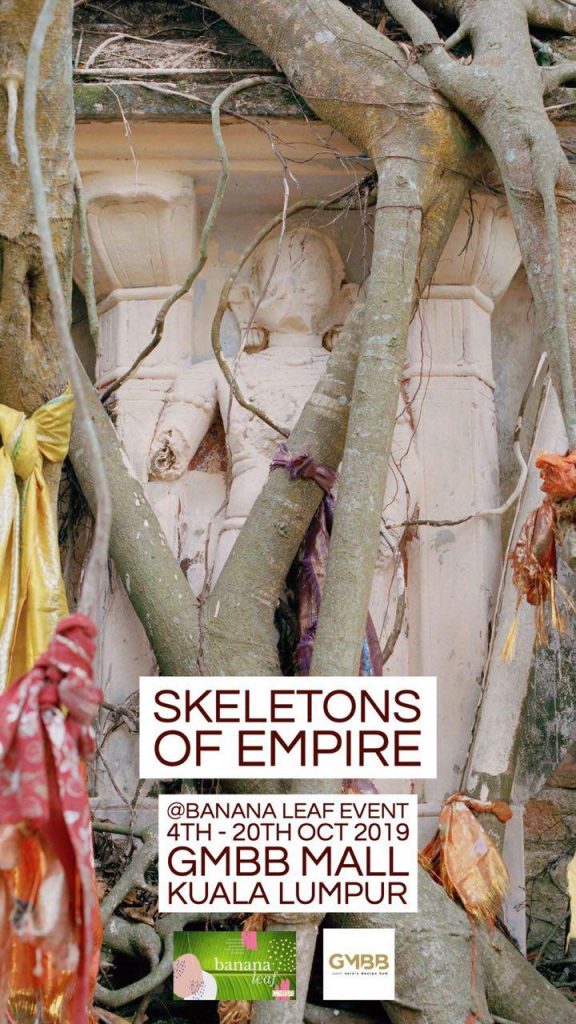

Mogan’s project, Skeletons of Empire, is on the Indian immigrants who came to Malaya to work in the rubber estates. He is currently exhibiting at Banana Leaf: A Celebration of Malaysian Indian Arts & Culture in GMBB Kuala Lumpur.

This is Mogan’s account of his journey through documentary photography, as told to the Varnam team.

From Mantin to Cardiff

I had a very normal Malaysian childhood. My schooling was done in Mantin and Seremban, and my mother is a single parent. After school, I took up software engineering. I went through a series of jobs before venturing into wedding photography in 2009. Specifically, Indian wedding photography.

I was doing well as a wedding photographer, with certifications by various organisations. But it came to a point where everything was automatic. I was not as passionate as I was before. A change was much needed.

I’ve always had a deep interest in telling stories. Coupled with my passion for photography itself, documentary photography seemed to be the natural next step. There was an opportunity for me to go back to university to study documentary photography. I jumped at it. Soon after, I found myself traveling to University of South Wales in Cardiff to further my studies in documentary photography.

Documentary photography was no walk in the park

I’ll admit, it was not the easiest decision to make the change to documentary photography, and to go back to university. It took a lot of adjusting and learning, but I was open to it, and that helped.

The thing with documentary photography is that it is really a different way of thinking, conceptualising and visualising the pictures I was going to take. There is also a lot of research that goes into the pictures, and interesting techniques like the use of archives and conceptual framework.

The thing with documentary photography is that it is really a different way of thinking, conceptualising and visualising the pictures one has to take.

And then, the BBC

The year was 2016. I was still getting into the groove of things in university when I was commissioned by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) to shadow and photograph legendary documentary photographer Martin Parr. It was a fantastic experience. This was an eye opener for me, I got to witness how documentary photographers work in the United Kingdom.

I was commissioned by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) to shadow and photograph legendary documentary photographer Martin Parr.

The icing on the cake was when my image was featured in BBC Creative’s Photography Exhibition. This took place in July this year, and it was a result of a collaboration between BBC Creative and Elephant Magazine.

Rubber

I was doing some research on my great grandfather last summer, for a project in university. His journey to Malaya piqued me, but there was not a lot of documentation. The immigrant communities in the Western world are laden with documentation – there are letters and photographs. In Asia, this isn’t the case, just as it is for our Malaysian Indian community.

The immigrant communities in the Western world are laden with documentation – there are letters and photographs. In Asia, this isn’t the case

I found some reports and archival material on the topic and this inspired me to do a project about the Malaysian Indians. It is a lot of history, but I wanted it to be relatable to today’s Malaysian Indian.

There was one factor that stood out during my research, and it was rubber. It is the reason the South Indians came over to Malaya. So I came up with a bigger body of work pertaining to rubber.

There are two chapters so far, and Skeletons of Empire is the the second chapter. This involved a lot of thinking, and I’m not going to lie, it was a challenge. The whole project took me 6 months and two trips to Malaysia to complete. It’s no joke trying to document something that isn’t there anymore.

It’s no joke trying to document something that isn’t there anymore.

It is a project that’s close to my heart. I have presented Skeletons of Empire at Goldsmith University, London. The event was organised by fellow Malaysian arts creative and curator, Kevin Bathmanathan, and it was called Decolonial Earth. It was something else!

There isn’t a lot of conversation about post-colonialism in Malaysia

I do enjoy working on themes like post-colonialism and immigrants. I mean, my ancestors were immigrants. Unfortunately, there aren’t may stories about immigrants here in Malaysia. It is rather complex because the Indians and Chinese have assimilated and there is plenty of talk about unity.

The conversation about being an immigrant and being part of a diaspora in a country that was so heavily colonised is almost nonexistent here.

This is our history, so I think it is important to see how it shapes our identity. The problem is, colonialism is very divisive. My job is to basically tell both sides of the story, and let people form their opinion. That is what being an artist is, if you ask me. You let people form their own perceptions about your work, and there is no right or wrong.

The problem is, colonialism is very divisive. My job is to basically tell both sides of the story, and let people form their opinion.

When two artistic minds meet

When I was taking pictures for Skeletons of Empire, one image I wanted to feature was of three Indian women. You see, I had come across a beautiful black and white picture of three Malaysian Indian women during my research for the project. The photograph was taken by the British when we were colonised. The three ladies are adorned in traditional outfits, but it was evident that they didn’t have a say in what to wear or how to pose. It was all instructed by the colonisers.

I wanted to photograph three Indian women, in whichever way they want to be portrayed, the power handed back to them. For this, I roped artist Ruby Subramaniam in.

When she told me that she would like my work featured in Banana Leaf, I decided to return to Malaysia sooner than I had initially planned to. Honestly, I am ecstatic about Banana Leaf! I mean, I have exhibited this piece of work during my graduation, and our Malaysians deserve to see it as well.

Banana Leaf – possibly the largest gathering of Malaysian Indian artists

The fact that Banana Leaf is a project by Malaysian Indians, for all Malaysians is absolutely amazing! I don’t think there has been an art exhibition done by Malaysian Indians on this scale, simply because of the numerous forms of art on display.

Also, while most of the artists are active on social media, there is nothing as engaging as having an exhibition where people can come up to you and talk to you about your work. It gives a really great insight into what Malaysian Indian artists are made of.

Mogan Selvakannu’s series of photographs, Skeletons of Empire is currently exhibiting at Banana Leaf: A Celebration of Malaysian Indian Arts & Culture, in GMBB Kuala Lumpur, up to the 20th of October. Keep up with Mogan’s snaps on Instagram here, or drop by his website here.

https://varnam.my/events/2019/12855/banana-leaf-a-celebration-of-malaysian-indian-arts-culture-a-must-see-art-exhibition-this-deepavali/

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook or Telegram for more updates and breaking news.