We’ve always highlighted talented Malaysians in our features. This March, we’re going to amp it up, in conjunction with International Women’s Day, with features on the many amazing Malaysian women who have made our nation and community proud. Enjoy!

There was once a young girl, who on her walk back from school, could smell the spices wafting from her house. They called her the girl with the yellow hands because she always helped her mother grind tumeric at a nearby mill.

Christina Arokiasamy has come a long way from her yellowing digits. Born and raised in Kuala Lumpur, this chef, spice expert and cookbook author was declared Malaysia’s first-ever official Food Ambassador to the United States.

Christina hosted The Malaysian Kitchen which aired on The Cooking Channel. The show was a hit, reaching over 80 million viewers across the United States. Her efforts helped place Malaysian in the top 3 flavor trends in America by The National Restaurant Association. She is continuing her crusade to make Malaysian food a household norm around the world, starting in the United States. She is currently based there with her family.

The Varnam team speaks to Christina about her journey with spices, her love for food and her perception of Malaysian cuisine.

Varnam: Your relationship with spices has been something that’s been simmering from childhood. How has it evolved for you?

Christina: Form a young age, I have found spices to be fascinating. My mother was a spice merchant. She would add beautiful layers of spices to food. We even used it in our medicine cabinet. It was magical for me to be around spices as a child. As I grew up and found that I had to cook for myself, I realised that I was drawn into this industry, the arena of flavours and food.

V: Tell us about your journey to chef and cookbook author.

C: After graduating with a degree in public relations, I began working in that sector. But I wasn’t enjoying it, work became a chore.

So I went abroad at a young age and learnt how to cook. I received professional culinary training and went on to work as a chef consultant at the Four Seasons Hotels in Thailand and Bali, Indonesia. After getting married, I lived in Hawaii. Every summer, I would go back to Southeast Asia to keep learning and to refine my skills in cooking.

On my many trips, I realised that nobody was cooking the food that I wanted to cook. I decided to start teaching cooking classes. The more I taught, the more I learnt from the American people about how they wanted to extend their own pantry. It then dawned on me, people in the western world didn’t know much about spices or flavour.

V: Was writing a book the natural next step for you?

C: No! I never imagined myself an author. It was only when the publishers in New York approached me to do so. I was in Washington at the time. They said, you’ve been teaching classes, will you try writing a cookbook?

The publisher then assigned me an agent, I didn’t even have to look for one on my own. Like a parent, the agent guided me with writing my cookbook. With my heart, I penned down all that I’d learnt. And that’s how the The Spice Merchant’s Daughter came to be. It was listed as top ten cookbooks in the USA by National Public Radio in 2008. It also earned a starred review on Publisher’s Weekly, and was featured on the Associated Press, The Wall Street Journal and The Boston Globe.

Cookbooks aren’t just a collection of recipes. They share a person’s values, their culture, including little anecdotes like why the mother cooked that on a Friday, why people eat on a banana leaf and why close it a certain way. It tells a good story that touches a heart. It brings the reader on a trip.

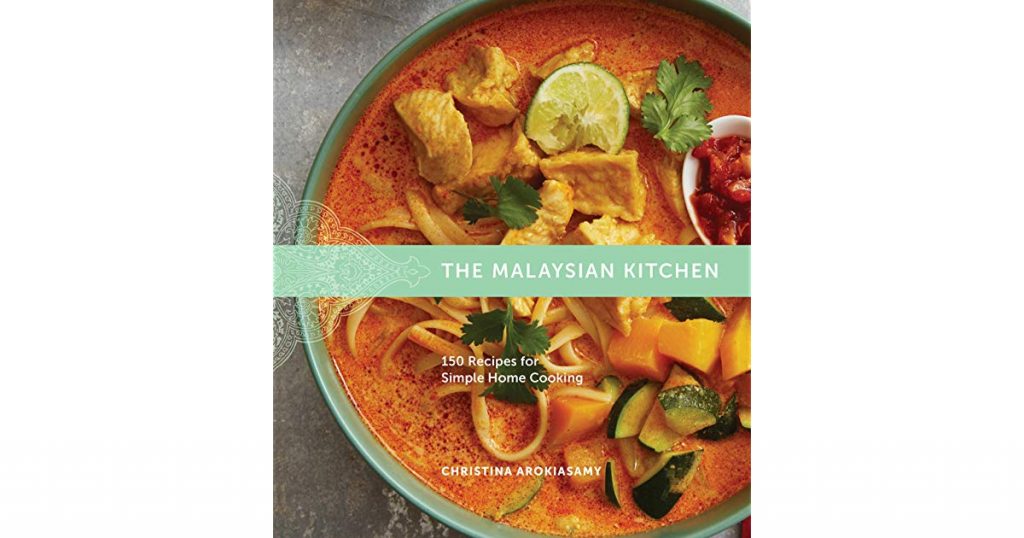

V: Your second cookbook, The Malaysian Kitchen: 150 Recipes for Simple Home Cooking also reached spectacular heights. It was featured in People Magazine, Oprah.com and awarded Amazon’s Top 10 Cookbooks of 2017. How do you feel, seeing your book reach such great heights?

C: It humbles me. My life in Malaysia was a struggle. I grew up in the era where it was “Chinese wanted” or “Malay wanted” in all the job advertisements. I didn’t conform to that. I want everybody to be given a chance based on their value and merit.

I made my way to the US and every time I worked on something I would put so much effort into it. I would put in days of research before coming up with an article. So when my work appeared on Oprah.com and NBC, it was so humbling. It was all respected publicity, I never paid for any of it.

Every time I look at that, it reminds me of where I come from, my roots. This trade that I had learnt from my mother, the information I acquired from my Southeast Asian family has made it so far. Its very important to reflect on that.

V: You speak a lot about bringing Malaysian cuisine to the kitchens of America. And you do this by introducing new ingredients, one by one. Why do it this way?

C: You know, in Malaysia, you don’t need to go to the market, the market comes to you on four wheels, or you could walk to the pasar malam. You’ve got curry leaves and pandan in your garden as well as Babas and Alagappas in every supermarket. We take all of that for granted.

You need to think about the average American who doesn’t have access to all of these when introducing a new cuisine to their kitchens

Here in the US, if you want lemongrass you need to go to a Thai shop. For tofu and soy sauce, you need to visit a Chinese shop. Yellow noodles here are presented full of chemicals and congealed oil in plastic wrapping that comes from China. Spices are exotic and they are only for the rich, as a tiny bottle the size of your palm costs north of $8.

I take things that they already have like cumin, peppercorns, chilli powder, tweak the way they use it. And immediately, the response is, “Wow, my chicken tastes different!” Bit by bit, this is how you get Americans to fall in love with your cuisine. In my second cookbook, there are recipes for laksa with fettucine and mee goreng using spaghetti. People can come back home, mix sambal ulek with mayo and make a delicious dip for their chicken wings.

V: Malaysian food gets bashed a lot because of how unhealthy it is. What’s your take on this?

C: I’m going to be fair, I agree with it. The way Malaysians cook unhealthy. Anyone who is reading this interview needs to realise that our health is the best investment we can make.

Lets deconstruct a dish. Rendang is made with shallots, garlic, lemongrass, galangal, chilies, woody spices and coconut oil – all these ingredients are actually good for you. When you cook rendang, if you are cooking it whole and eating all these aromatics, the health benefits are right there.

When you eat outside, however, they use palm oil, often congealed and old. The meat may be a cut of poor quality and often not refrigerated properly. Everything is simmering in oil and it morphs into a dish that is so high in cholesterol and long chain fatty acids that are bad for you. The healthy ingredients that you’ve started out with is gone.

V: So you’re saying the Malaysian homecooked food is healthy, not what is available outside?

C: The food we cook at home would remain healthy. If we go back to the foundation of how this food was to be cooked, Malaysian food is not unhealthy, it is fabulous.

But in Malaysia, we always want to go out, because we feel the restaurants are more delicious than what we get at home. Perhaps it is, but it isn’t as good for your health.

When I look at Malaysians presenting the food, everything has one inch of red oil floating atop it. I wonder, why would anyone need so much oil? Why not prepare the same dish cooked very lightly in oil? No person outside Malaysia is going to invest or earn the respect of Malaysian food if it is going to be so unhealthy.

It’s not like you cannot taste the flavours of something just because there is less oil in it!

Don’t destroy an ingredient for the sake of the flavour, compromising your health. This is how we can sustain our cuisine, we can teach people that Malaysian food is healthy. Any food if you think about it, we can always come up with a way to make it healthier.

V: What is the biggest myth when it comes to Malaysian food?

C: (Pauses to think) When people talk about Malaysian food, they always think Malay, Chinese and Indian cuisine. This has been translated to the rest of the world. But why can’t Malaysian food be also the kind of food that actual Malaysians eat? What is cooked at home on a daily basis.

Look at your Chinese neighbour. Do you think her parents cook the same way the Chinese restaurant near your house does? Your neighbour’s food is a little different, but why isn’t that Malaysian food?

I think we put so much emphasis on the usual Malaysian dishes like nasi lemak, satay, rendang and roti canai that we have narrowed Malaysian cuisine down to that. But we are boxing ourselves in by doing that. What your mum makes at home when you were growing up, that’s Malaysian food too.

V: This would render Malaysian food to be limitless!

C: There really is no limit to it. Malaysian food is unique to the people of this land, their knowledge, their way of life and how they cook with what they have. It doesn’t have to be nasi lemak to be Malaysian.

There is a dish that I call ‘Slow Cooked Tomatoes in Coconut Cream Sauce’. As a young girl, I knew it as sothi. I wanted Americans to try this dish, but nobody understood when I said that. This particular dish isn’t usually regarded as Malaysian food. But why not?

Every single cookbook that has come out of Malaysia only has the same style of recipes. We will never create, we will never evolve, because we forget to recognise that we all came to this land, we made this place our home and we made food our own style and it is unique as we are. And that is also Malaysian food, it has to be respected for that.

Honestly, Malaysian food isn’t just a mixture of cultures, it is how the people in Malaysia eat in their own homes too.

Visit Christina’s website here. Keep up with her on Facebook here and on Instagram here.

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook or Telegram for more updates and breaking news.