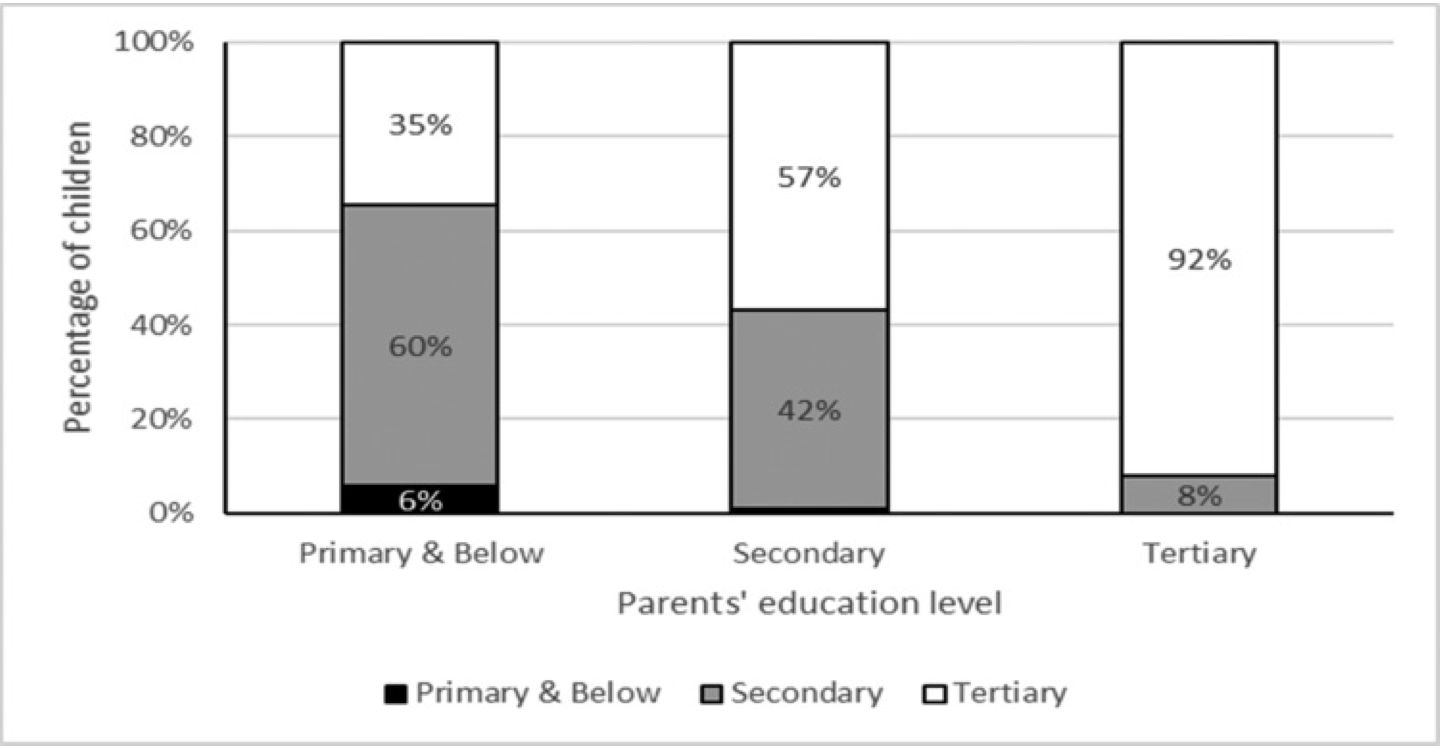

Would a child’s attainment of greater educational and career mobility transform into a higher income disparity, wealth and better quality of life in comparison to their parents?

Despite the increase in official income disparities, the absolute earning gap between Malaysia’s top 20 percent and their countrymen has continued to decline. Based on the average between the revenues of the middle-class and the broader population of poor Indians the statistics drawn were unreliable.

It shows as if the Indians were doing well but, a wide cluster of them were still classified as poor and have somehow allowed poverty to last for generations.

When compared to other ethnic groups, income inequality is significantly higher in the Indian population. It has been further compounded by a sub-culture of gang-related crime and violence. The root cause can be seen among the unstable Indian communities and systemic problems linked to marginalisation (of the Indians).

The children had higher real income than their parents in each income class, with the exception of children born to parents in the top quintile. The pattern in ethnicity is almost constant. In absolute terms, one in two children had higher incomes than their parents, but the number was even higher, at eight in ten, for children born to parents in the lower quintile (i.e. parents in the lowest income group).

However, only one out of ten had higher earnings than their parents for children born to parents in the upper quintile. Adjusted for inflation, the median income of children compared to their parents was 12 percent higher. Children with the lowest quintiles had 40 percent more revenue than their kin, compared to the second and third quintiles with around 13 percent.

Perhaps the most eye-opening aspect of this novel entitled, The Malaysian Indians: History, Problems and Future by Muzafar Desmond Tate had illustrated and penned down some essential points about our Indian community.

The division of Indians in the country were compartmentalised as below:

(1) Elite, composed of professionals, top officials of the government and senior executives of leading private firms;

2) An upper middle class, educated in English, composed mostly of government servants;

(3) A lower middle class, vernacularly educated, consisting of traders, school teachers, journalists, smallholders, all mainly outside the government service;

4) Government sector employees, PWD, medical facilities, railways, docks and large city municipalities, and private jobs, particularly on estates.

Tate concludes that the major problems of the Indian population remained the same in 2000 as they were before 1957. The segregation between the middle-class Indians who were working in plantations and the inability of the NEP to help Indians below the poverty line were still obvious.

The poverty crisis, along with current challenges faced by urban squatters, has become a sort of accepted way of life, pushing the community further into greater marginalisation and discrimination. During the British colonial period, a large number of Indians who arrived in Malaya comprised mainly from the Dalit caste in India who were hired as contract laborers for tin mines and agricultural estates, mainly on rubber plantations.

From the moment they arrived in Malaya, they were ‘virtually debt slaves,’ having to work off the cost of their travel and recruitment under the contract scheme. Their salaries were so meager that their whole term of employment would be stripped away.

The New Economic Policy (NEP) was established based on the per capita income of the population of Malaysia, India, China, and abroad. It has helped the Malays and Bumiputera out of poverty and managed to establish a middle-class community of Malays. However, what we didn’t know was that the Indians weren’t a homogeneous group, and they were made up of numerous groups that came to Malaya in many batches.

Steps to help our Indian community:

In the first place, compulsory education must be implemented among our community as it empowers everyone. When we think about education, the first thing that strikes our minds is acquiring knowledge. In this competitive world, our Indian community needs a good education to be able to thrive. Modern culture is focused on individuals with a high quality of life and awareness that helps them provide better solutions to their problems.

There need for better arrangements to benefit the poor Indians, from homes to schools to jobs, so that we can eliminate poverty among the Indian poor within one generation and elevate them to the middle class through education and support, much as we did under the NEP for the Bumiputera.

At the same time, youth training programs such as special training programs can be undertaken for displaced Indian youths concentrating on urban life skills, including technical and entrepreneurship skills. The only channel for social change is not solely based on traditional schooling. For underachievers without basic college credentials, special hands-on skills training programs should be prioritised and emphasised more on.

Presently, MySkills Foundation is engaging many Indians youths by providing vocational training programmes in hopes of developing life-long skills in order for these youths to find employment or simply kick-start their own trade.

Regardless of colour, race, and faith, this thread is an eye-opener for all of us. The plight of our people has to be embarked on seriously by the government, as it gears to become a developed nation.

What are your thoughts on the development of the Indian community? Are we still in bondage or there have been some changes in our standard of living and quality of life? Share your views with us in the comment section.

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook or Telegram for more updates and breaking news.