Putrajaya was all about rubber estates and oil palm plantations, until it became a hub for the federal administrative centre with elegant urban designs that adopted Islamic architecture.

Malaya provided more than half the world’s rubber in 1920!

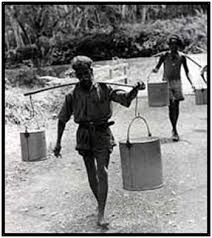

Much of the plantation population were South Indians (mostly Tamils) who came here during the British colonial period to work on coffee, sugar and rubber plantations and to construct infrastructure such as ports, roads and railroads, if you can remember your History subject.

They needed more manpower to keep up with the demand for higher production of rubber. They couldn’t persuade the Malay community (because they’re already farming and fishing) to enter this industry and needed to establish good ties with the Malay rulers.

And since they were still operating firms and being hired for tin mining, they did not ask the Chinese community either. So, they selected the Indian labourers in the rubber estates to do some boring and exhausting jobs.

The Indians were also recruited as civil servants and supervisors of the plantations. And that’s how we got our workers at the plantation.

Prang Besar Estate was then acquired by the Malaysian Government as the site for the administrative capital of the nation. The property near Kajang, strategically located between Kuala Lumpur and Sepang’s new international airport, will be developed into an urban centre housing the Federal Government’s offices.

The township of 4,000 that we all know now as Putrajaya was then expected to be completed by 1998 and to house almost half a million individuals.

In the 90’s some of the rubber plantation workers lost their jobs as the demand for their labour was reduced due to mechanisation and the change from rubber to less labor-intensive) oil palm. Apart from that, the plantation was bought to be used for urban expansion. And none other than Putrajaya was part of this metropolitan expansion.

In order to do that, a workspace that was free of traffic jams such as those seen in KL and the need to be also housed in one location was desired by the government. Prang Besar was selected after some shortlisting of potential locations for three main reasons:

- It was close to the then newly formed connection to the highway and airport.

- Prang Besar stood under one estate, so it was easier and cheaper to acquire the land.

- An opportunity for expansion was provided by the North-South corridor.

So in August 1995, the construction work began in this township. Putrajaya Holdings Sdn Bhd demolished the plantation where all the workers earned their livelihood and an eviction notice was issued to them.

The question remains:

Where could they possible go after being issued with a 48 days eviction notice?

Due to the shocking implementation it severely caused over 400 families from four estates to lose work, homes and temples (177 of whom were from Prang Besar, the biggest estate of the four). Some of the families were also said to have lost their land which they had bought to rear cattle and raise vegetables as early as 1975.

About 10,000 low-cost housing units was included in the Putrajaya Master Plan. But, aside from being “world-class” and “wired,” their position in Putrajaya and the efficiency of the units was, umm, unknown. The government originally made it mandatory for developers of all housing developments to build at least 30 percent ‘low-cost’ units (not more than RM25,000).

Although it seemed like the former workers were not rewarded with any such units, they were actually relocated to the Taman Permata flats in nearby Dengkil.

The 10,000 supposed “low-cost” units, evidently, were valued at RM49,000! It was not sufficiently affordable.

The workers owned the land before the expulsion which they had used for cultivation and farming for their own use and for extra household income. But after they sold their farm and had no land to own in their flats, this shifted, so their additional income and savings went dry.

They did not possess the requisite skills for technical jobs to which the qualified talented Indian nationals were drawn to, due to the fact that they have been in the agricultural sector for years. They were left with no choice but to take on general work such as security guards, cleaners, gardeners, operator workers, truck drivers with the lowest wages (RM 700).

Their wages did not match the increasing cost of living, and while no ex-plantation worker is a stranger to hard labour or low pay, the other necessities available for free in the estates were no longer free (like food crops that peeps could just pluck from).

In 2013, a ton of safety and health problems arose among the community after the flat occupants had to live in tents due to the cracks, unstable floors and rotting walls in the flat unit.

The plantation workers from Prang Besar that were obviously made up of the Indian minority have yet to receive full justice. They were evicted of their own land with the promise of the moon and stars, but many still remain in the run down flats without compensation of any sort.

As the community awaits a better life ahead, some have probably or are attempting to improve their state of affairs, are left with no choice but to do so on their own without expecting any help from the government. Lest we forget, that the rubber industry was one of the twin poles of the economy on which Malaysia’s present day wealth was founded.

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook or Telegram for more updates and breaking news.