Capital S.E.X. Let’s talk about it, shall we? Sex, for the longest time, has been and still is, considered a taboo subject amongst Asians. And I think this is especially true for Indians. It is even more true for women, who are taught when they’re kids and then constantly reminded throughout their lives that their bodies are like fine French wine — expensive but loses its value and begins to go bad after uncorking. Women shouldn’t watch porn. Women shouldn’t masturbate. Women shouldn’t express their sexual desires. And on and on and on with the outright ridiculous notions. In fact, it’s best if we all pretend that the birds and the bees don’t even exist.

Which is one of the reasons why Ram’s Peranbu is brilliantly shocking. It doesn’t just address a female teen’s very natural sexual awakening, it explicitly addresses sexual awakening of a female teen with spastic cerebral palsy… through a non-judgemental lens. And how a father, single after his wife left him for another man, processes the goings on and does what he thinks is best to take care of his less abled daughter. This is a bold film that deserves to be applauded, admired and dissected. It’s made not just to entertain, but to move you and provide a perspective.

Director Ram (Thanga Meengal, Taramani) has said that his films are always built on a thesis. Or more accurately, he stands on top of a thesis which helps him find his story. In Peranbu, his thesis is nature and it’s divided into many chapters — 10 if I recall correctly. It starts of with nature is hateful (earlier in the film, Amudhavan’s hateful mother asks him why he doesn’t just get rid of his “sickening” daughter, who at times yells and cries uncontrollably), ends with nature is compassionate and explores everything in between. But it also makes us question why we blame nature when life doesn’t go our way. Why do we label nature cruel if we’re born with disabilities when nature itself doesn’t see us as less than, only our fellow humans do.

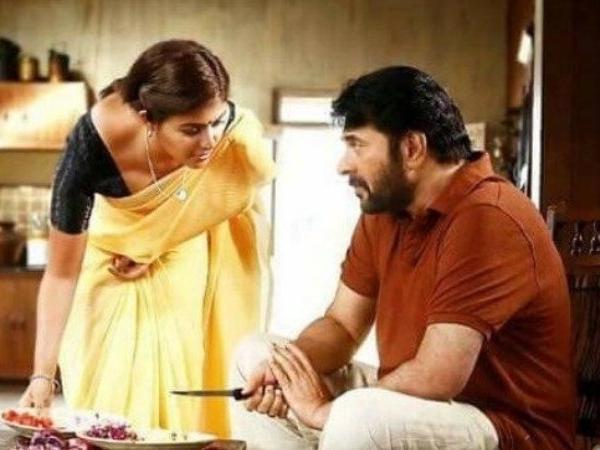

The single father named Amudhavan, is played by Mammootty, who puts aside his stardom completely to embody a character who is lost in his role as dad and mom, and suffering, unable to find his footing. We start in a city, sardine-packed, noisy and cruel. Amudhavan’s wife has left him, his mother hates his daughter and his neighbours are unhappy with her noise. He takes his daughter and migrates away from the cruelty of the city to the serene, breezy and kind countryside of what looks Kodaikanal. As Amudhavan puts it, it’s a “place where humans don’t intrude and pigeons don’t die.” There he desperately tries to understand and connect with his daughter, Paapa (in a transformative performance by Sadhana).

But nature has other plans.

Peranbu is a thought-provoking, raw, emotionally charged drama and I can’t stop thinking about it. It isn’t a masala film. It isn’t bursting with big emotions where characters overtly cry their eyes dry as the music swells. It isn’t even a film in the vein of say, Pariyerum Perumal, which is grounded and gritty but contains mainstream masala elements. This one’s quiet and emits an art-house vibe.

Think about the scene where Amudhavan tries to communicate with his daughter in the dining room. He sings and he sings. First in Tamil, and then in Hindi. He forgets the lyrics. He tries again. He dances. He jumps around goofily, trying to get his daughter to smile. The camera is at a slight distance, at a lower angle, swaying gracefully and steadily from left to right but never closing in. Ram doesn’t cut away, opting instead for a long take.

It’s as if we’re sitting on the floor and observing. A closeup shot would have given Mammootty the room to do “more acting” and given us the chance to examine his performance in micro detail, but Ram is going for something else. Something more impactful. Here we’re a powerless passive observer, unable to lend a hand. It’s a painful scene to watch. Eventually, Amudhavan concedes defeat. He’s truly lost.

Or what about the scene in the second act? — this is after he’s able to build a connection with his daughter. Amudhavan wakes up in the middle of the night to realise that his daughter who’s sleeping beside him has bled for the first time. He doesn’t say anything, but you can feel his heart letting out a resounding sigh. He leans against the wall in defeat. Imagine hiking for two days thinking you’re about to reach the peak of Mount Everest, only to realise that you’re finally merely at the foot. The real shit is just about the begin.

Peranbu is that kinda movie. It’s real and grounded. There’s a quietness to it. Silence is a character. Theni Easwar’s cinematography is gorgeous but never flamboyant. A gentle breeze as opposed to the mighty Zephyr of say, Tirru’s cinematography in Petta. The same can be said about the music too, which doesn’t reach out and guide your emotions. Here, the music is atmospheric. Unlike his Maari 2 album which is gloriously showy and incredibly catchy, in Peranbu his rich musical score and soundtracks recede into the background working only to help Ram bring his incredible thesis to life.

It’s interesting how Ram juxtaposes the stillness of nature (even the opening credits sequence is quiet) with the roughness of Amudhavan and Paapa’s life. Later, in the second half they go back to the city and mother nature keeps toying with him. But now, the city seems crueller and noisier than it was before. Keyword: seems.

Maybe the problem isn’t with nature. Maybe the problem is with Amudhavan, who on the surface seems like a gem of a man, one who never judges anybody for their wrongdoings. (When a husband and wife con him out of his house rendering him homeless, he says they probably have a good reason for doing so.)

But what if Amudhavan is a slightly selfish man? What if he took his daughter away from the city and into the middle of nowhere under the guise of helping her, but in reality is doing it for himself at the expense of his her? After all, a growing teenager requires human interaction more than she requires a pet horse. But Amudhavan continues to trap her in proverbial cages. Even in the city, he locks her in a room while he heads out for work, leaving Sun TV and some window slits her only access to the outside world.

This too ties back to the thesis. Sex is natural and it cannot be suppressed. When Paapa starts feeling urges, things get trickier for Amudhavan. And the film gets even more gripping (and at times uncomfortable) than it already is. Ram doesn’t sugar coat anything. This is a film that normalizes sex. It shows you why it’s important for parents to educate children about sex from a very young age. It is a liberal film that is sure to ruffle some feathers and that’s a good thing. It also has a transgender character who has a prominent role and an ending that is revolutionary, though slightly unearned.

This is merely Ram’s fourth film but he exudes the confidence of Leonardo da Vinci with a paintbrush. He shows immense restraint, tone perfectly controlled from scene to scene, only allowing bigger emotions loose at precise moments. The scene where Paapa makes out with the TV which has a good looking actor on display comes to mind. Amudhavan closes the door behind him and Mammootty lets his emotions flow, thumping his head in defeat. It’s fantastic filmmaking and fantastic acting. We truly are in a new age of Tamil cinema. An age of FILMMAKERS (not named Mani Ratnam and K. Balachander) who are auteurs. And Peranbu, man, Peranbu is the first unmissable movie of 2019.

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook or Telegram for more updates and breaking news.