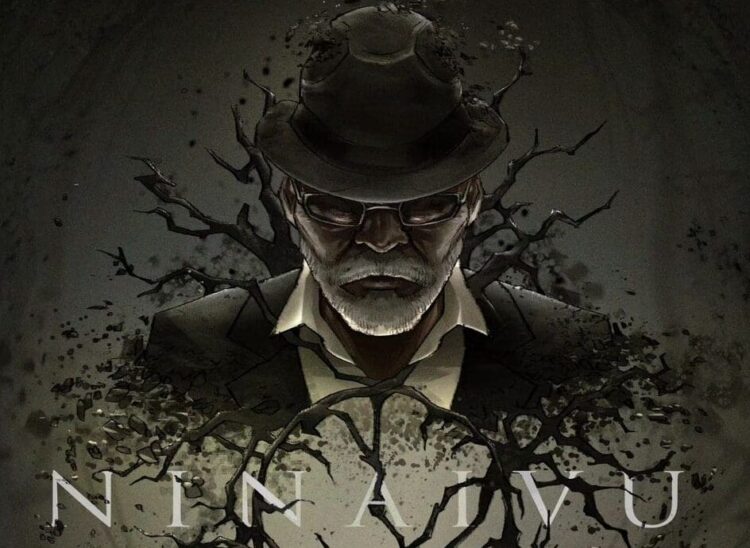

Ninaivu (Memory), directed by Kavivarmen Vigneswaran and co-written by himself and Eric Low, is a short film that very achingly and lucidly unfolds the haunting emotions of time and memory. The film very meaningfully explores the complexity of memory and consciousness through the main characters of the Old Man, played with outmost depth and sensitivity by Rajendran Perumal, and the defiant and inquisitive character of the Boy, wonderfully portrayed by the young S. Pravin.

Landscapes play an immensely significant role in this film, which is largely focused on the solemn dialogues between the Old Man and the Boy. Often, films that have fewer characters and are driven by dialogue can feel as if the characters are mere shells that are forced to express the thoughts of the writers, but Ninaivu is a film with such soulful and human writing, combined with the incredibly fleshed out acting of Rajendran and Pravin, that each dialogue, along with the visual characterization, is captured with utter severity and sincerity.

The usage of limited space in the film, which predominately takes place in a cinema hall, in the forest by large trees, and in a decaying house, is a reflection of the finiteness that life gifts one with. Even so, the fact that limited space was utilised in the film never made the film feel monotonous, repetitive, or claustrophobic; instead, each space materialised as an entity of its own in the film, one that not only bore the characters but also was in conversation with them and the film as a whole. While lifeless films only exploit landscapes as inanimate objects, in Ninaivu, the landscapes come alive, speaking in their own language, and making their presence known and felt.

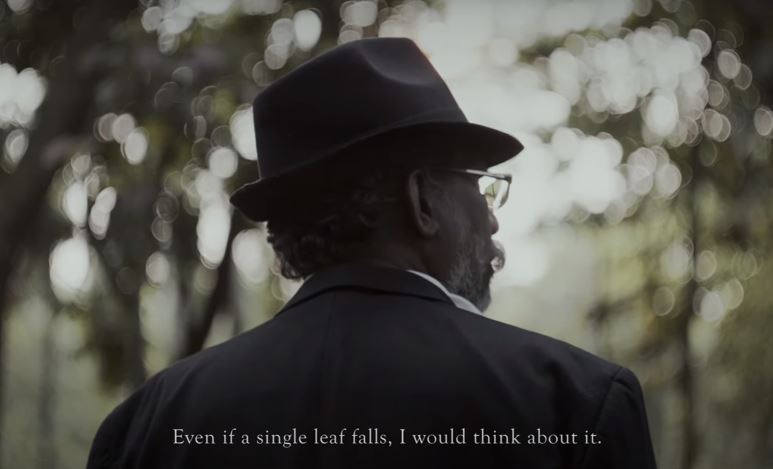

In the sanctum of nature, the Old Man ponders if they, the trees, feel pain over the withering of their leaves, and soon affirms that the tree is in fact brave enough to let go of a part of itself. The tree here is a painful yet precise metaphor for life—for the long life that the Old Man has endured. To age is to wither, to decreate, and to destroy parts of oneself. The ritual of ageing is not just about the material changes that ruptures through the body but also a guttural and cathartic metamorphosis of the soul, where one perpetually becomes and unbecomes, like leaves of the tree.

The young Boy on the other hand, although inquisitive about the Old Man’s thoughts, does not find it important to introspect about nature. He is almost thoughtless about the passing of time and about the earthly severing around him. However, the Old Man because of his age, and the stagnancies that come with the withering of youth, could sit idle; he could contemplate the world around him because he had surrendered and felt the weight of time on his bones. The young, because of the vigour they possess, have not yet grasped the reality that time is a finite entity, constantly slipping from their grasp. When confronted with the withered leaf, the Boy reminiscently says that “the longer we think about it, the more it destroys us”, the meaning for which will become even more cemented to us once we learn later on in the film that he is an orphan, an abandoned child who cannot introspect about his environment as stopping to think of his loss would consume him.

Deconstructing Domesticity

In a decaying architecture, the domesticated space of a house is slowly being decomposed by the earth, and it beckons to the Old Man because his body too will soon become one with nature. As the walls are adorned with fungus, mosses, and wildflowers, while entire sections of the house is open to the view of the forest, we see how a space that was once occupied by the daily activities of civilised humanity has become decrepit and inhospitable for modern life. Time not only devours the physical fleshed shell of humanity but also destroys the finite creations of the masses.

The young Boy too feels as if space is calling towards him, as in the epitome of time and the eclipsing of the body is awaiting him. When the Old Man says that it is dangerous to follow strangers, the Boy retorts that the Old Man doesn’t seem all that strange. This interaction mimics again how one deals with the prospect of ageing and the chaos of time, where we are led to become strangers in our futures, yet sometimes the person awaiting us at the end of our lives is not all that menacing or monstrous but a merely mundane and vulnerable creature.

It is in this space that the Boy shares that he is an orphan, and the reason he sells kacang on the streets is to preserve the memory of his father, who also did the same job when he was alive. To this, the Old Man sorrowfully shares the bitter truth that no matter how intensely we want to protect our memories, some will eventually, and inescapably, fade from our consciousness.

In the empty cinema hall, the audience, along with the Old Man finally realise why he constantly goes to the cinema. The Old Man who presumably suffers from memory loss, goes to the cinema to remember his late wife. As we don’t see her as an aged woman, perhaps it could be interpreted that she had died young, leaving him with only the memories of her throughout his lonely life. When the Old Man finally realises the truth, he mysteriously disappears into the void of the cinema hall, leaving the young boy only with his broken watch. The fact that the entire film begins and ends in the empty, possessing space of the cinema hall hauntingly echoes how existence is a cyclical entropy.

The broken watch that is left behind is also an affliction of the dialectical system of time. While humanity has invented a form of scale to understand the progression of time, they have not grasped what this entity is or have even evolved to control it. The watch, in a sense, echoes the helplessness of humanity that tries to have a semblance of control over time, while the malfunction of the device reveals the horrid truth that time can never be tamed and is, in essence, a chaotic axiom. The fact that it was the Old Man who was holding onto it painfully conveys how he was desperately clinging onto something that had long been reaped from him. In the end, as the Old Man disappears into the hollowed darkness of the cinema, we see that all that is left of him to be held by the Boy is the broken watch, as an heirloom of chaos waiting to be experienced by another.

Memory and Indentured Tamils

On a closing note, although this subject was not explicitly stated in the short film, the topic of memory, remembrance and Indentured Tamils in Malaysia are an intricately interwoven wound. The subject matter of memory is an endangered emotion within the predominantly working class Tamils in Malaysia, as expressed by the character of the Boy, who are mostly descendants of indentured labour. The memory of slave labour, of caste, of colonialism, of displacement, and of identity are all hauntings that leave them in abandonment and alienation, just like the state of the Boy at the end of the film.

The relationship that the Old Man and the Boy share are not just merely metaphysical but is also a tangible and tormenting tie to the history of oppression. Both of them are lonely, lost, and grieving, bearing the burden of displacement not only from land but also from memory and history. The Old Man’s reminiscence and his amnesia are a reflection of how even when the younger generation inquires into the lives of their forefathers, there is only a pale, fleeting reflection of the truth. Working-class Tamils are reaped from the opportunity to study, analyse, and find resolutions for their liberation; instead, they are left, much like the Boy, in darkness, desolation, and disillusion. To remember and to be remembered is the most profound and necessary human act, yet because of the monstrosity of capital, millions are left to be buried into the void while their descendants are left to desperately recollect the history of their lives.

Kavivarmen Vigneswaran’s Ninaivu is a melancholically aesthetic film that very earnestly balances its story with a complex and sensitive script, acting, and cinematography that all come together to create a thought-provoking film. While some filmmakers can be narcissistic and pretentious when it comes to conveying existential subject matter in cinema, Kavivarmen’s earnest direction and the contribution of the entire team have instead brought a story to life with integrity and humane warmth. Their handwork illuminates the bright and exciting path of not just the creators of the film but also the future of cinema in Malaysia.

The short film can be viewed on Youtube.

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook or Telegram for more updates and breaking news.