The Bhais, directed by Mohamed Shafie, is a first-of-its kind, satirical and thought-provoking mockumentary that earnestly and intriguingly expresses the lives of contemporary Tamil Muslims in Malaysia through the film medium. Although primarily a mockumentary in genre, with an aloof and sometimes ambiguous structure, Shafie’s The Bhais is an achingly necessary artistic expression of the Malaysian Tamil Muslim identity and the dialectical thoughts and emotions that the community possesses within itself. The micro-series is deeply textured with writing and acting that complexly and humorously articulates perspectives on the multiplicities of being Tamil, bearing critical notions upon culture, ethno-religious politics in Malaysia, and the absurd monotony of daily life under neo-colonial capitalism.

The Director: Mohamed Shafie

“I’m endeavoring to portray the story of our community from a different perspective or at least something to think about.”

A native of Kuala Lumpur, Mohammed Shafie is a fourth-generation Malaysian Tamil whose ancestors hail from a village called Panaikulam located in the eastern part of Ramanathapuram. Apart from his own two grandfathers, one who worked at a painting office in Kedah and another who owned a kedai runcit, which was colloquially referred to as an ‘ottu kadai’ by Tamil Muslims, there were many other migrants from Panaikulam who had settled in Malaya and Singapore, forming a transnational link between the two lands.

Shafie, who studied film and broadcasting, is currently working as a freelance filmmaker and editor. He shared how a reason for his captivation of the visual medium had been to use the device of cinema to express the complex and myriad nature of the Tamil Muslim community in Malaysia, which is often reduced and condensed to merely mamak restaurants. Although the Tamil Muslim and larger Tamil community in Malaysia have an over 200-year history in Malaya, these histories are very rarely critically understood by the larger public, including the Tamils themselves.

Shafie also explained that Iranian cinema in particular had entranced him into the world of film for their ability to both express their culture and ideology through the film medium, despite facing much censorship and restrictions by the Islamic Republic. Some of the works that engaged him were Jafar Panahi’s ‘Offside’ and Kamal Tabrizi’s ‘Marmoulak’. Much like many other forms of subaltern artistic expression, Iranian cinema does remain as a source of hope among many that, while repression exists, art can and should be instrumentalised to demand one’s right to humanity, and to be complete and soulful in consciousness. It’s interesting to note that while the Malaysian state has been influenced by the “Islamic Revolution” of Iran, the younger generation of Malaysian creators is seeking influence from the very cinema that was birthed, at least in part, as a counter-reaction to that movement.

Shafie spoke of how the owner of the channel ‘Amis House’ had asked him to keep the channel alive with new content and that is a reason for the creation of the mockumentary micro-series. He also noted that the spirit of the mockumentary was inspired by Donald Glover’s Atlanta, which had been a widely praised series that dealt with a multi-dimensional, satirical, and critical diction of the African American community, which, much like the Malaysian Tamil Muslim community, had been mandated into a superficial social understanding. It was with this need to express the realities of his community that Shafie took it upon himself to not only direct but also to write, shoot, and edit the whole mockumentary himself.

“The actors are like my brothers. I’ve known them personally for many years.”

Shafie’s actors are composed of people whom he proudly and fondly calls as his brothers: Nazeer, Muzzammil, Faizal, Saiful, Asiq, Imran, and Mat Noor. The director expressed his utmost gratitude towards them for graciously being part of this project despite having commitments such as work and family. Alongside them, Shafie has also extended his gratitude towards Azaad, whom he has come to know over the past few months and who has also been a addition the micro-series.

Identities: India Muslim, Mamak, Thulukkar

In the first episode itself, audiences are introduced to the many ways in which the Malaysian Tamil Muslim community is referred to. There is the term “India Muslim” and “Bhai” which are used among themselves; there is the term “mamak,” which is said to be used by Malays to refer to them; while it is widely known that the word mamak comes from the Tamil word maama, the cultural origin of it is quite unknown the masses. The practice of referring to Tamil Muslim men as maama, by Muslim and Non-Muslim Tamil alike, has its roots in southern Tamil Nadu, where many Malaysian Tamils are from. As these southern Tamils migrated to Malaya, they brought over this cultural vernacular to this new land, where the term maama had transformed into mamak, once non-Tamils began using the term.

Although the term Thulukkar is used as a slur against Tamil Muslims in Tamil Nadu, Shafie counters this notion by portraying that for Tamil Muslims in Malaysia, the term is not derogatory but instead perceived as a signifier of the origins of Tamil Muslims. While it is true that through the many trade establishments with the Ottoman Turks and Arab Muslims, the religion of Islam spread through Tamil Nadu, and that there is a wide belief that all Tamil Muslims are descendants of Arab and Turkish Muslim men who had intermarried with local Tamil women, this belief does not encapsulate the diverse roots and existence of Islam in Tamil Nadu. For instance, independent researcher Kombai S. Anwar has explained how during the 7th century, when the prosecution of Tamil Jains and Buddhists was taking place, many of these prosecuted people had converted to Islam to protect themselves. The cultural connection between Tamil Muslims and Tamil Jains is evident in the manner in which many Tamil Muslims have retained Tamil Jain vernaculars such as palli (masjid), nombu (fast), thozhugai (prayer), and perunaal (eid). Moreover, just as in medieval times, in the modern period, Islam is used as a way for Dalits (lower castes) to escape their oppression from the caste system and form their own self-respect. One of the most historic conversions in Tamil Nadu’s modern history was the 1981 Meenakshipuram conversion, where nearly 600 self-determined Dalits had mass converted to Islam as a defiance against the caste enslavement imposed on them. All these stand as critical examples of the Tamil Muslim identity, which cannot merely be seen as just being descendants of Muslim Turks and Arabs but instead should be understood as how the Tamil masses themselves consciously chose to convert to Islam in order to escape the enslavement of caste, and live as liberated and dignified human beings. The existence of both the Tamil Muslim and Tamil Christian communities is a profound predicament, not just of a people being mere descendants of foreigners but rather, more importantly, of how the most oppressed, abused, and exploited members of Tamil society have taken the conscious social and political decision to free themselves from the incarceration of caste through conversion. While it is known that conversion alone cannot abolish caste, the struggle of the subaltern to liberate themselves, through any means possible, is a noble cause that we must respect.

“Maybe, some who use it against us might find it satisfying to call us Thulukan, but it doesn’t affect us in any way.”

In Tamil Nadu, the term thullukan is deliberately thrown against the Tamil Muslim community by Hindu extremists, in order to uproot them both genealogically and culturally from the Tamil lands because their very existence reveals the sociopolitical inequality that is deeply embedded in caste-possessed Tamil society. While within the borders of Malaysia too, Shafie proclaims that some might refer to Tamil Muslims by the slur, he affirms defiantly that how others perceive the community does not affect them.

Oorachum Mayirachum: Dichotomies of Land and Landlessness of the Tamil Diaspora

“Often, I find the need to know our Indian hometowns arises from the fact they want to gauge our background and how to look upon us.”

Criticisms on Culture

“So does culture dictate society, or is the society dictating the culture?”

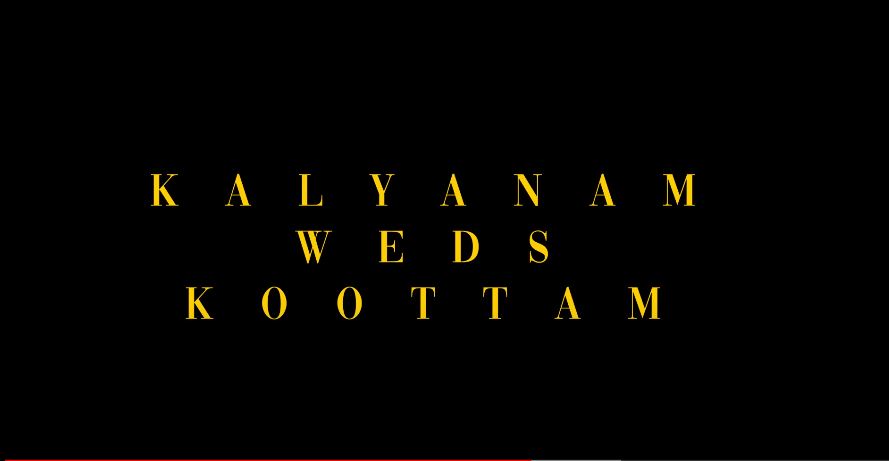

The characters, while dramatic and absurd, also exhibit introspections and criticisms of their own against the perception of “culture,” and the narrative decreates the entity of culture that comes into contradiction with self-perceptions of characters. Shafie introduces two important elements that express the core of the Tamil Muslim culture, the first being weddings and the second being language. When the concept of marriage is analysed at its root, we must understand that, through the rise of private property, the concept of marriage has metamorphed into an administration that authorises the union of land, wealth, customs, ethics, and values. Through this understanding, we can see how, within the Tamil Muslim community, just as in many other communities, for there to be marriage, there has to be a wedding at its genesis, to publicly announce and celebrate this alliance of ideologies. Shafie conceptualises that the wedding, being an expression of Tamil Muslim culture, is often demanded to be extravagant and audacious, built on the belief that this form of lavishness is innately part of Tamil Muslim culture, putting an immense burden on young people to spend well over their means to protect and project this impression of wealth. Not having an expensive wedding is seen as going against one’s own identity, community, and customs. When these perceptions of culture are demanded from those who are already exploited by the drudgery of wage labour, Shafie’s narrative roots itself in a critical question of the authoritative relationship between society and culture.

Additionally, the grandeur of the wedding is not only exhibited in the scale of its spending but also in the number of its guests, so much so that the scene satirically shows the words Kalyanam Weds Koottam, hilariously harmonising the metaphorical wedding of both the economic administration of marriage with the sociopolitical consciousness of the masses. The act reaffirms that marriage is not merely a private union between families but a public spectacle of cultural and ideological reproduction. The innate need to have a crowd at a wedding also exposes the dialectical nature that binds the Tamil Muslim community together: that despite differences and conflict, one should always nurture fraternity among one another regardless of differences. But it does beg the question: what happens when the contradiction between society and self gets too great? How does one remain bound to it through that alienation?

Additionally, the grandeur of the wedding is not only exhibited in the scale of its spending but also in the number of its guests, so much so that the scene satirically shows the words Kalyanam Weds Koottam, hilariously harmonising the metaphorical wedding of both the economic administration of marriage with the sociopolitical consciousness of the masses. The act reaffirms that marriage is not merely a private union between families but a public spectacle of cultural and ideological reproduction. The innate need to have a crowd at a wedding also exposes the dialectical nature that binds the Tamil Muslim community together: that despite differences and conflict, one should always nurture fraternity among one another regardless of differences. But it does beg the question: what happens when the contradiction between society and self gets too great? How does one remain bound to it through that alienation?

On Language

“In a culture where we accept cursing and shaming as normal, I find it weird that profanity is seen as a more culturally corrupt practice.”

Another aspect that is foundational to the Tamil Muslim community is the ancestral cord they bear with their mother tongue, Tamil. In this satire, audiences get to witness the diverging perceptions the community holds about how language should be expressed in terms of ethics and morality. In the episode Namma Culture, when a young man is seen to have used a foul word, he is immediately met with a stern character, scolding him because he has not only tarnished the purity and sanctity of the Tamil language but also the dignity of the Tamil Muslim community.

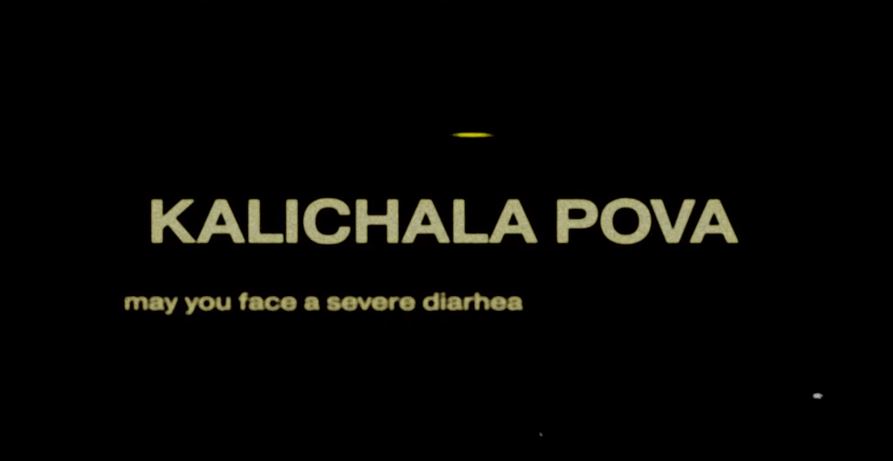

Shafie’s writing inverses this idea that language should be incarcerated into a tightly controlled and monitored vernacular and instead juxtaposes this morality policing by exposing that those who righteously use “Pure Tamil” still weaponize the language to shame and curse others, an act far more violent and debaucherous than harmless profanity. While some characters in the scene offer sanitised alternatives to swear words, with words such as ariveketta mundong, moodevi, and kalaichala poova, the undercurrent idea that Shafie attempts to explore is not so much the vernaculars of the language but rather the hypocritical governance that is implemented by the community on the ethical expression of self.

The self-righteous moral high ground that some members of the Tamil Muslim community have built around themselves also introduces the audiences to the familiar vanity that every other community in the world has about themselves, which is that they and they alone are the bearers and protectors of “true culture.”

“We also share the same reasons and necessities as the rest of the Tamil community to hold the language at an important pedestal.”

Apart from that, Shafie also explained that the Tamil language is deeply important for the Malaysian Tamil Muslim community because it is the only language that allows them to communicate with their elders, who most often only know Tamil. The language is a cord that roots people in the community together, across generations and across the diaspora, to the motherland. Shafie also noted that, just as the wider Tamil community, the Tamil Muslims too bore the significant responsibility to protect and nurture the Tamil language. Because through her purity and through her profanity, the Tamil language is an inherent and instinctive part of the Tamil Muslim identity and culture.

On being Tamil and being Muslim in Malaysia

“Across time, we gradually shed those inhibitions and comfortably identify as racially Indian. At least for the majority of us.”

While the mockumentary mostly adheres to a satirical and aloof tone throughout the micro-series, a significant shift in this expression occurs in the episode Peace and Polambals, where the characters earnestly speak about the marginality of the Tamil Muslim community in Peninsula Malaysia. Their alienation, in a way, is a reflection of the fragile and dysfunctional way in which state-sanctioned identities are authorised in Malaysian society. When popular social understanding of identities such as race and religion is dictated by constrictive and controlled reactionary politics, many in this society, like the Tamil Muslims, find themselves in a situation where they have to absolve and eradicate parts of themselves to be accepted. For all its performance of unity in diversity, Malaysia is a dysfunctionally racist state where identities have to be segregated and segmented into superficial categories that both obliterate the forms of diversity within the accepted categories of Malay, Indian, and Chinese in Peninsula Malaysia while also severely alienating those, like the Tamil Muslims, who find themselves not fully being able to identify with any of the available categories. The narratives articulate how in schools, Tamil Muslims are made to choose between identifying as either Malay or Indian, even when neither category truly captured who they were completely. Some would choose one or the other, and some would accept the narrative of their classmates, that they were either mixed or had parents who had converted to Islam. All this goes to show the extent to which outside forces hold the power to determine what a person in Malaysia should identify as, while diminishing their entire root. One of the oldest mosques in the world, the Palaiya Juma Palli Masjid, constructed in 630 CE, lies in Tamil Nadu’s Kilakarai. In contrast, the oldest mosque in Malaya is said to be Masjid Kampung Laut, and according to the Islamic Tourism Centre under the Malaysian Ministry, it was constructed in 1676, several centuries after the construction of the first mosque in Tamil Nadu. Yet the centuries-old distinct heritage of the Tamil Muslims is denied any form of earnest public acknowledgement and understanding in Malaysia, resulting in this alienating identity crisis imposed on Tamil Muslim children by the Malaysian society and the Malaysian state.

In Peninsula Malaysia, identities are one-dimensional and packaged commercially for easy access; a Malay is always Muslim, and an Indian is always Hindu. Even the formation of the identities of “Malay” and “Indian” is purposefully oversimplified, deluding the masses from truly comprehending the complexities of not just what it means to be Malay or Indian but also the other ethnic and indigenous identities of this land. Shafie articulates that although in their younger days, Tamil Muslims face these alienations, particularly from their Malay friends, they gradually grow to accept themselves wholly and completely for themselves and their roots as a people.

While in collaboration with the reactionary state, there are Tamil Hindus who try to forcefully Hinduize the Tamil identity in order to protect the caste hierarchy, and there are Malay Muslims who weaponize Islam to further their Malay supremacist Islamist politics. Amidst all this chaos, Shafie assures that for the Tamil Muslim, neither their ethnic nor their religious identity can be tyrannized by any of these forces.

“I don’t think both hegemonies affect our identity. Neither do the Tamil Hindus dictate our Tamilness, nor do the Malay Muslims dictate how we follow Islam. Islam is Islam for all. So we do not face that from both the hegemonies.”

In the episode Narcissist, we get to see once again how chaotically fragile Malaysian society can be as we see the nation deal with the urgent crisis of a man selling “Nasi Kandar Babi.” Shafie places two characters with opposing views in the scene, one representing the ignorance and insecure statement made by a popular Indian Muslim representative in a public space regarding a newly opened shop called “Nasi Kandar Babi” and the other representing a rational and normal person who truly can’t even comprehend what the issue is here, which was the thoughts of many Malaysians when this nonsense issue unfolded. Shafie’s narrative, while exploring the marginality of the Tamil Muslim community, does not fear pointing out certain members that cause strife within their community and Malaysian society as a whole. The “Nasi Kandar Babi” issue revealed how one individual’s narcissism deliberately mutates into national uproar, shaping even more divisions and reactionary sentiments among Malaysians of various ethnicities.

The Obscurities of Bumiputeraness

“There is so much ambiguity around how this is implemented which requires further civil intervention to sort out.”

Perhaps the mother of all turmoil in Malaysia, the Bumiputera status, is a powerful entity that every Malaysian and non-Malaysian has to come into contact with when living in this wretched state. In Peace and Polambals, there is a brief mention of how there are community-led attempts to get Malaysian Tamil Muslims the Bumiputera status. Shafie explains that while there are some Bumiputera concessions that are available to Tamil Muslims, the system is so ambiguous in its implementation that it needs more government intervention to systematise it. Earlier, we could see how in Peninsula Malaysia, how inefficient and alienating the racial categories of Malay, Chinese, and Indian can be, but the god of all inefficiencies and alienations is the confusing and aggravating apartheid-like segregation between Bumiputera and non-Bumiputera. Even within the category Bumiputera, there are many contradictions, such as how Orang Aslis that are categorised as Bumiputera do not receive the same amount of government aid as the Malays. As for the native Borneans, there are many indigenous ethnic and tribal communities that still struggle to even gain citizenship, and even those who are documented as Bumiputera severely lag behind in development when compared to Malay Bumiputeras in Malaya. Even so, there are many non-Bumis’, like the Tamil Muslim, who are demanding that they too be given the Bumiputera status. In this predicament, Shafie expresses his earnest intrigue of whether gaining this status alone can liberate Malaysian society from inequality.

“I do wonder if the Bumiputra status will end all qualms about racial equality for all communities? It’s probably a start. Maybe.”

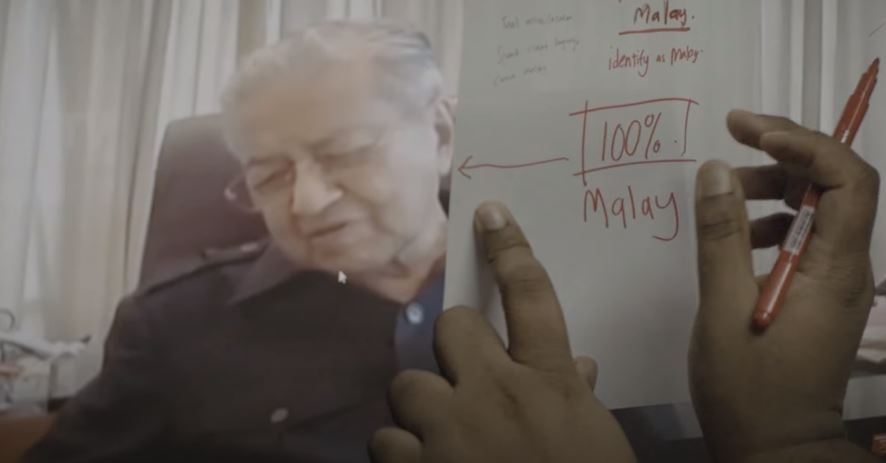

Becoming Malay

In the episode New Year, New Me, the narrative expounds further on how the imposition and laceration of identities in Malaysia don’t just affect Tamil Muslims but also Tamil Hindus. Even with the convoluted state of the Bumiputera status, and even while tormenting non-Malays and non-Muslims on a daily basis, Malays still try to propagate the sweet promise that with just enough assimilation, one can simply become Malay and all sorrows will fade. Shafie had cast his good friend and filmmaker Gogularaajan Ranjendran, with whom he had have previously worked with on several projects together like K For Kannadhasan, The Next Call, and The Fowl Play, as the role of a Tamil Hindu character who farcely tries to become Malay. Through this narrative, the audience gets to learn just how shallow and superficial the Malay identity is publicly perceived and projected to be. That simply through learning the Malay language and the Malay customs and annihilating one’s ancestral roots, anyone at all can simply, become Malay.

The narrative also delves into the hypocrisy of certain Malays, who, while discriminating against Tamils and demanding they completely assimilate into Malay society, express great admiration and excitement over consuming Kollywood films from Tamil Nadu. Shafie notes that this engagement of Malays with commercial Tamil Nadu films is also a practice of ignoring the Malaysian Tamil reality, as Kollywood films only represent self-serving entertainment for Malays rather than any form of connection to the reality of Tamils both in Malaysia and Tamil Nadu.

“I do not think Malays watching Tamil cinemas has anything to do with their acceptance towards the Tamil community in Malaysia because the Tamil cinema stars in those movies are not demanding for the rights of the Tamil community in Malaysia.”

In the same episode, we are also introduced to the realities of non-Muslim Tamils, who, like the Tamil Muslims, experiences the alienation that comes with being an ethnic minority in Malaysia. The narrative also interestingly explores the eclipsing experiences of both the Tamil Hindu and Tamil Muslim identities and the fraternity that is formed through them.

“I think both the Indian and Indian Muslims share a very close bond. Our friends’ circle often overlaps. We make fun of each other openly and we discuss each others’ culture openly. We often find ourselves on the same boat, so the bond is naturally necessary.”

Speaking to Gogu about his relationship with Shafie and his experience working on this project, he shared how the friendship Gogu has gained with the director has brought a new perspective on the Tamil Muslim community to him. Gogu expressed how, after Shafie, the true humanness, warmth, and beauty of the Tamil Muslim community were understood by him, saying how much he enjoyed being in their presence while they spoke to each other about things that were foreign to him, yet still, he would fondly and inquisitively listen to them all. When asked about his thoughts on the project, Gogu shared that it’s a necessary story that has to be told by the community itself. He had also mentioned that the two of them would often talk about the celebrated Malayali writer Vaikom Muhammad Basheer together. Gogu remarked that while Shafie is still in the early stages of his film career, he hopes that one day the young director could create magnificent works for his community, just as Muhammad Basheer had used his literature to speak of the deep and meaningful lives of Malayali Muslims.

Speaking to Gogu about his relationship with Shafie and his experience working on this project, he shared how the friendship Gogu has gained with the director has brought a new perspective on the Tamil Muslim community to him. Gogu expressed how, after Shafie, the true humanness, warmth, and beauty of the Tamil Muslim community were understood by him, saying how much he enjoyed being in their presence while they spoke to each other about things that were foreign to him, yet still, he would fondly and inquisitively listen to them all. When asked about his thoughts on the project, Gogu shared that it’s a necessary story that has to be told by the community itself. He had also mentioned that the two of them would often talk about the celebrated Malayali writer Vaikom Muhammad Basheer together. Gogu remarked that while Shafie is still in the early stages of his film career, he hopes that one day the young director could create magnificent works for his community, just as Muhammad Basheer had used his literature to speak of the deep and meaningful lives of Malayali Muslims.

Against Class Conflict

“Our identity is more nuanced than the impression that our economic class has given others, which is what I intend to capture through my stories.”

The episode Elite Bhais delves into the nature of class and how alienation within the Tamil Muslim community rises when upper-class people are excluded from the community because of their class identity. Audiences witness how the ‘Elite Bhai’ is continuously excluded and literally pushed aside by the rest of the characters, who are portrayed as being from the middle and working class. The ‘Elite Bhai’ is relentlessly questioned and scrutinised, not because of who he truly is but because of who others perceive and falsely determine him to be, because of his class identity. They assume he cannot speak Tamil and that he would not eat in regular mamak shops, and while all these assumptions are refuted through the narrative, he is still left abandoned by his community because they chose to believe in their lies more than his truth.

It is not often that a piece of media empathises with the upper class character, and the reason for Shafie doing so was because he wanted to address the nuances of identity and how class could not completely encapsulate individuals. Shafie elaborates that his community contains multitudes, and class can never define the plurities of his people. He shares how he has encountered many humble and well-meaning elite Tamil Muslims who bear no resemblance to these fallacies built up about them by the rest of the community. He wanted his narrative to be critical of these false perceptions of the upper class and to expound further on how dialectal the nature of identities is—one that cannot simply be buried and hollowed out by economic status. This relationship of class and identity was also introduced and explored throughout the microseries, showing that not all Tamil Muslims, as popular belief imposes, come from wealth; in fact, the majority of the narrative expresses that the community too struggles and faces marginalisation. What this episode implores is that even with the existence of upper-class Tamil Muslims, class is merely an impression and not the innate crux of the Tamil Muslim community.

Towards More Understandings

In this void of chaos, where metaphysical delusions of identity and root are forced upon us, it is important that we understand one another because the more we understand each other, the more the context of our own histories is revealed. The marginalisation of the Tamil Muslim community within wider culture and politics is the result of the complacencies and self-centeredness exhibited by other Tamils and Malaysians.

While on the surface, the mockumentary is comedically entertaining, the micro-series, on a deeper level, actually reveals something more uncomfortable and sinister about the entire reality of Malaysia and Malaysians. Although there is an obnoxiously vain self-glorification of diversity in religion, languages, ethnicities, and cultures in Malaysia, at the hollow pit of the entire masquerade is a mutilation of civilizations. As the people are ruled by state-authorised superficiality, the vast majority of Malaysians neither understand the truth about themselves nor the people around them. When the true depth and intricacies of the masses are suffocated with carefully constructed lies, the medium of genuine and earnest art usurps as a powerful instrument for everyone to unearth, reclaim, and forge their own narratives. Only through a deep understanding of themselves can the masses democratically progress as a society that understands completely and critically the substance and soul of those around us. In that vein, Shafie, although still early in his career, has created something that must and should be engaged with by everyone, because it is not only the story of his community, but a critical reflection of the society we all live in.

The entire mockumentary can be viewed for free on Youtube.

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook or Telegram for more updates and breaking news.