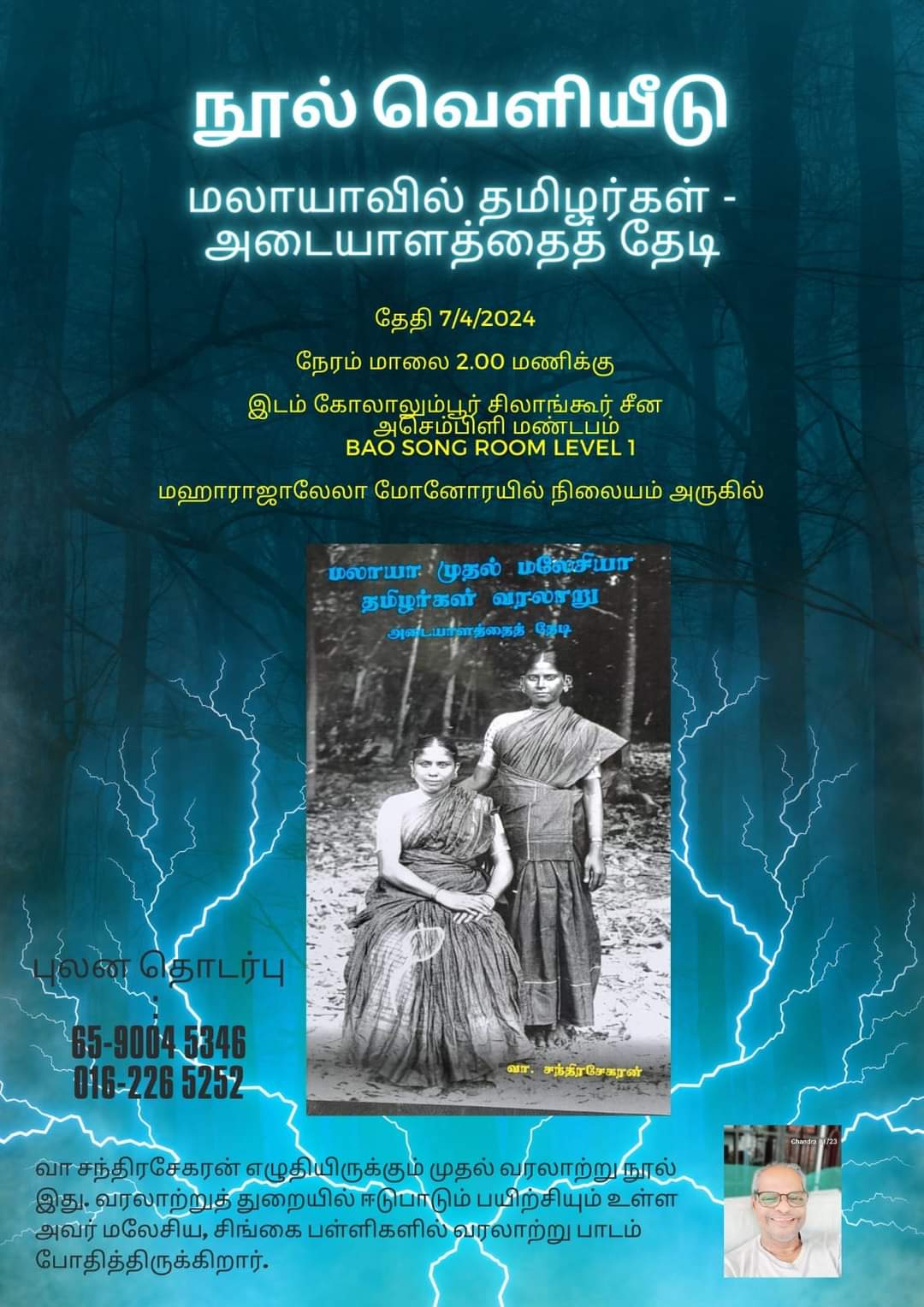

Tamil history, although an inseparable element of Malaysia, is something that has been ignored and conveniently forgotten by both the Tamil people and the larger Malaysian population. In an act of countering this narrative, Author V. Sandrasegaran’s latest Tamil-language book, titled Malaya Muthal Malaysia Tamizhar Varalaru: Adaiyalathai Thedi (Tamil History from Malaya to Malaysia: In Search of Identity) is an introspective work that delves into the personal interpretations of the marginalised aspects of Tamil history in the Malayan Peninsula, from the mediaeval period of Malay kingdoms to the anti-colonial liberation movements of Colonial Malaya up to the post-colonial entity of Malaysia. The book will be launched on April 7, 2024, at 2 p.m. at the Bao Song Room Level 1, KL and Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall.

Sandrasegaran expressed that his desire to write this book came from the urgent and necessary need to reclaim Malaysian Tamil history that has been buried and to also dispel the revisionist mythological tales spewed within the Malaysian Tamil community about their own origins. The former teacher shared how it is crucial that the young generation of today not be deluded by false glorifications about being descendants of the Cholas but instead critically understand the true progressive and even revolutionary history that their ancestors have forged in Malaya.

The Life of the Author

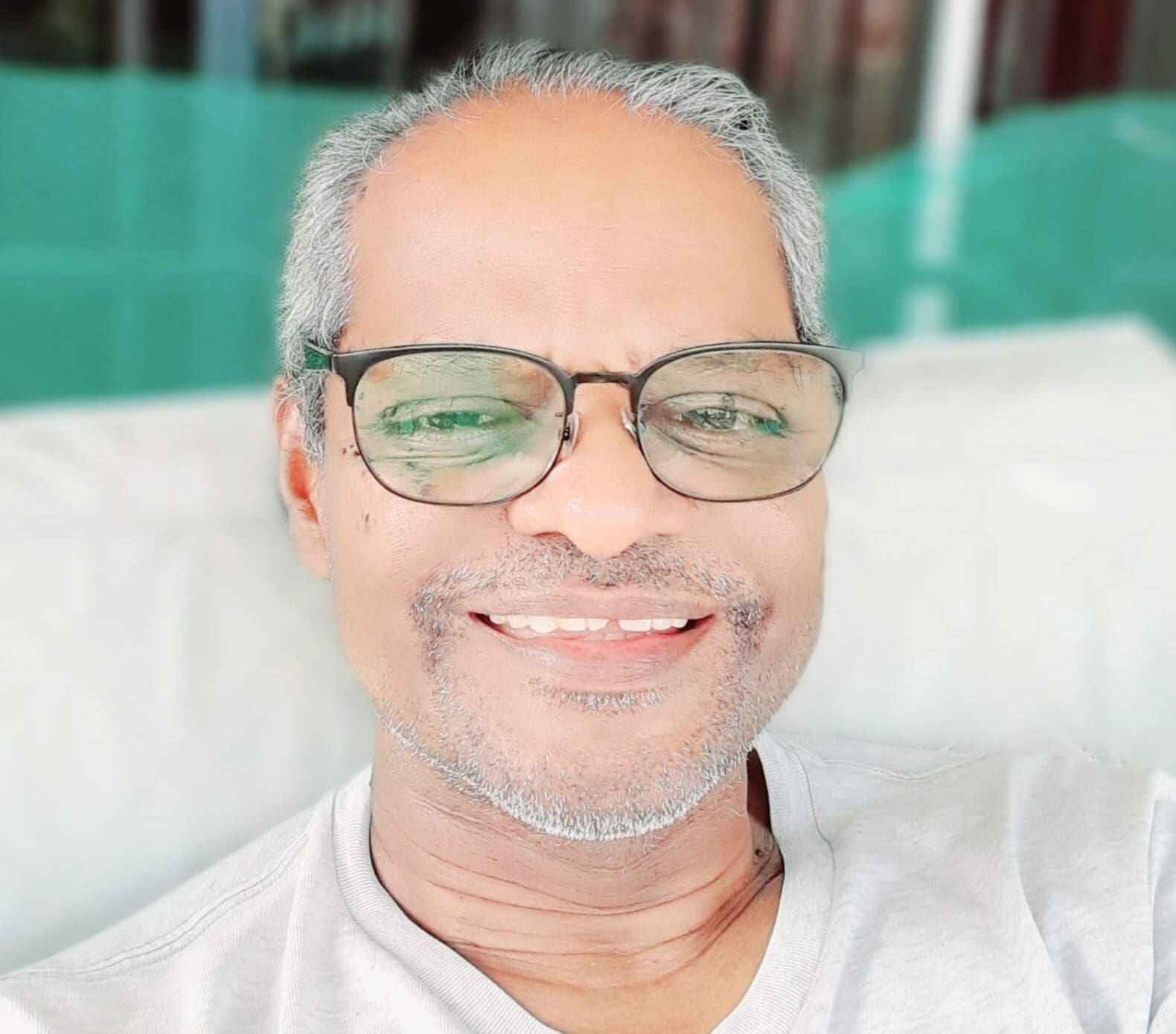

Penang-born V. Sandrasegaran describes himself as a rudderless boat that was always drifting at sea without much aim or direction. Although he was naturally gifted in academics, he was never inclined towards any field in particular until he was persuaded by his senior to complete his degree in humanities with education. He had spent much of his adult life as a teacher, from teaching for nearly 7 years in Sabah and then in Kuala Lumpur to finally settling in Singapore, where he currently holds permanent residency. Something that also inspired him towards pursuing a career in education was a trip organised by his university club that brought him face-to-face with the reality of the plantation Tamils in estates. He saw the actuality of the Tamil working-class community, and that evoked a sense of duty within him towards his people. Sandrasegaran understood that, through being an educator, he could both elevate the Tamil proletariat and also root himself closer to the Tamil community.

Sandrasegaran had begun writing, initially in English, the drafts of the current book in the early 1990s while he was teaching in Sabah, but due to the malfunction of his floppy disc, the file containing several chapters of the book had been corrupted and irredeemable. The incident had deterred his spirits from continuing to write, and he had put the idea of the book aside until 2020, when, due to the movement control imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, he had ample time to work on his writing. The book, which had been completed in 2022, went through several rounds of editing and gained feedback from trusted friends until it was decided to be released this year. Sandrasegaran shared that a revised English translation of the book will be released soon.

Introspections Against Revisionist History

The book was birthed as a way for Sandrasegaran himself to understand his own identity and his people’s place in the land of Malaya. He asserts that while this book draws extensively from credible research papers, books, and archival material, it is not intended as a conventional historical text. Rather, it is crafted as an interpretive and introspective narrative about from the histories of the Malaysian Tamils. Sandrasegaran also expressed his gratitude towards his friends, who had also guided him in finding sources and sharpening his thoughts on the subject matters of the book.

Sandrasegaran had expressed frustration at the many misconceptions of Malaysian Tamil history, which, due to the lack of many aspects of the history being understudied and existing research being inaccessible to the larger public, most Malaysian Tamils have a warped understanding about themselves, which is controlled by the opportunist mythologies spewed by those who have an agenda to corrupt the consciousness of the masses.

The first two chapters of the book speak about the historical context of the Bujang Valley civilization in Kedah, which is venerated as one of the oldest civilizations in all of Southeast Asia, along with the might of the Malacca Sultanate. While these two historical epochs are important to Malaysia, the Tamils often have a revisionist, mythological, and self-centred perception of these histories. Sandrasegaran’s book fights against this conventional foolishness among Tamils, who believe that it was the Cholas that began civilization in Bujang Valley and that Parameswara, the Hindu Palembang Prince, was a Tamil. These kinds of falsehoods are not only a shame to the integrity of the historical field but also a humiliating act that obscures both the history of Tamils and the history of Malaya and her indigenous people. His book, while struggling against the fantasies of revisionists, puts forth factual narratives of these histories and the sincere contributions that mediaeval Tamils have made towards the growth of these feudal landscapes.

The third chapter of the book explores the history of the direct ancestors of many Malaysian Tamils today, which are those Tamils who migrated to Malaya in the 19th century. This particular migration of Tamils was not just of indenture labourers, who did constitute the largest amount of the migrants, but also of white collar workers such as clerks, teachers, along with wealthy businessmen. When speaking about the available academic works that have been contributed by scholars like Sinnappah Arasaratnam and K. S. Sandhu, Sandrasegaran expresses both his gratitude for their tremendous intellectual labour and, at the same time, register vital criticism towards their lack of depth when it came to the caste question of the Tamils in Malaya. He says that while it is true that many Tamil indentured labourers had been from the lower castes, as stated in the works of S. Arasaratnam and K. S. Sandhu, Sandrasegaran cites that the East India Company records in Calcutta state that about 2/3 of Tamil indentured labourers had come from other non-Dalit sections of Tamil Nadu. He expressed that this black hole in their scholarship when it came to the diversity of caste among Tamil labourers had led to the popular myth in Malaysian society that all Tamils are from the lower caste, leading to caste slurs like “Paria” being thrown against the Malaysian Tamil community. He had also conveyed that because academically Tamils have been constrained under the hegemony of the “Indian” label, the particular history of Tamils is conflated with that of the Malayali and Punjabi migrations, without understanding that each ethnic group has its own history that diverges and contradicts the other.

Three Important Malaysian Tamil Histories

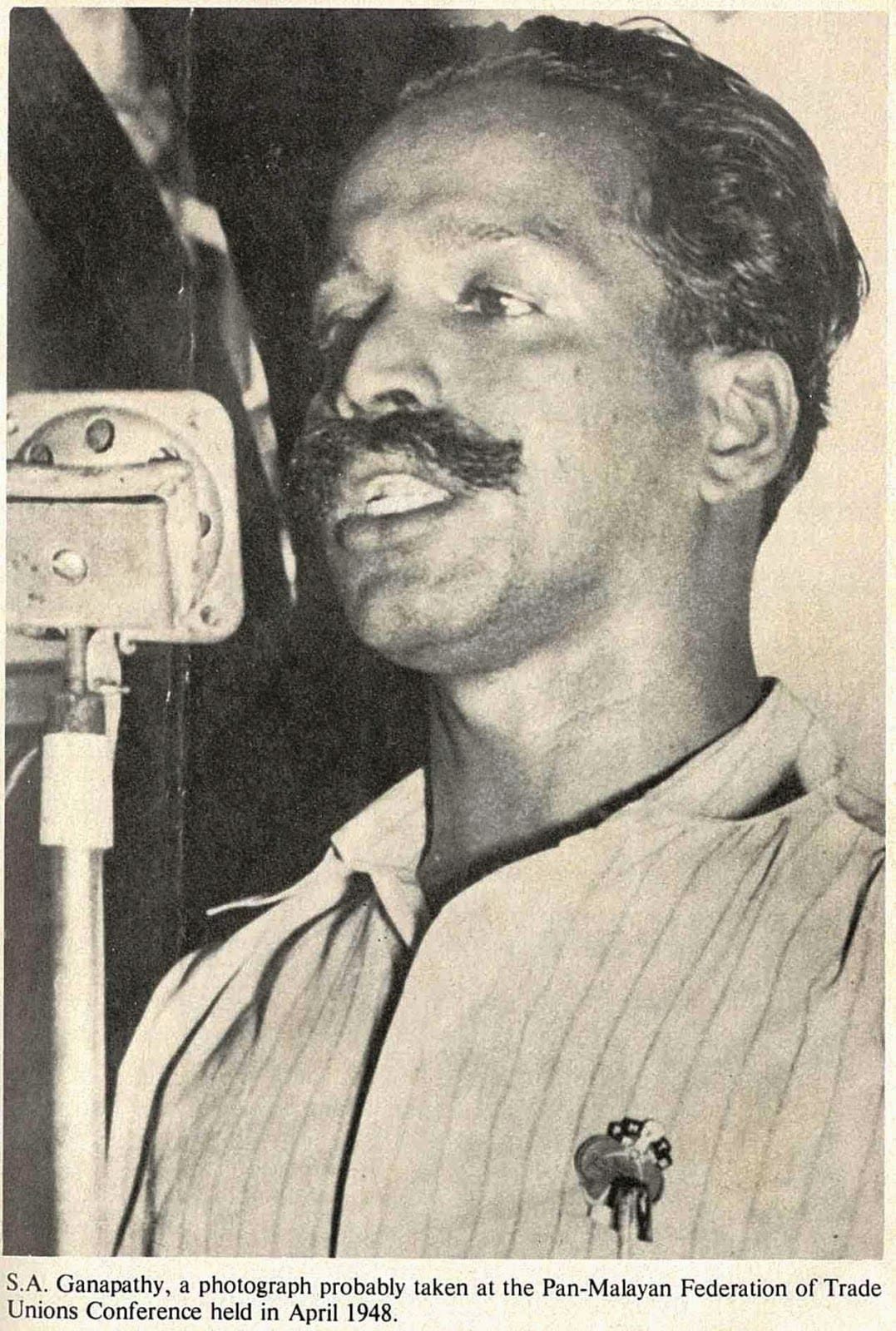

To Sandrasegaran, one of the most vital historical moments for Tamils in Malaysia was the 1941 Klang Strike, which is recorded as the first and one of the largest labour agitations in Colonial Malaya. The protest had seen hundreds of estates come together to fight for their rights as workers. This protest by workers was met with extreme violence by the army under the orders of the colonial administration, which wanted to suppress the rising revolutionary consciousness of the workers. The brutality and fear of the colonial government against the valiant workers had killed five innocent Tamil lives. When speaking about this particular history, Sandrasegaran articulated how this labour strike showed just how conscious the Tamil workers were of fighting for their own rights and dignity. He further expounded on how Tamils have been an intricate part of the workers movement in Malaya, paying his respects to revolutionaries like S. A. Ganapathy, who was the first president of the Pan Malayan Federation of Trade Unions (PMFTU) and an important leader in the history of Malaya’s anti-imperialist struggle.

Equally important to Sandrasegaran, was the Siam-Burma Death Railway, which had killed nearly 100,000 Tamils, along with the Malayan Tamil soldiers who joined Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army (INA) to fight for the liberation of India. The two events have a symbiotic relationship to one another, as Sandrasegaran pointed out that while the fascist Japanese were brutally killing and raping Tamils in the making of the railway, the Tamils in INA were fighting for an army that was allied with the very same Japanese. Sandrasegaran conveyed his conflicted feelings about the INA and the Japanese’s treatment of the Tamils, even stating that while he respected Subhas Chandra Bose, he saw the man as an accomplice to the Japanese. On the other hand, Sandrasegaran pointed out that the Tamils were valiant and critical enough to fight an armed struggle against British imperialism. Both the history of the labour movement and the anti-colonial movement in Malaya have the blood, sweat, and tears of Tamils rooted in them. He declared that Tamils were not spectators of history but active participants and pioneers of history on Malayan soil.

In the last chapter of his book, Sandrasegaran communicates his vision for the future of Malaysian Tamils, stating that they should stay away from trying to gain political representation and instead work towards becoming a community that is self-reliant and self-sufficient without having to beg from the government for concessions. Sandrasegaran voiced that all these years of Malaysian Tamil politics have seen only a hand full of Tamils in parliament that are only elected as tokenisms for the ruling elite, who do nothing substantial for the progression of the Tamil community.

Continuing the Search for Identity

Sandrasegaran’s book can be understood as both an introspection of the history of Tamils in Malaya as well as a criticism of the cultural and social understanding of history that is held by the Malaysian Tamil community and larger Malaysian society. The writer also expresses his disappointments towards the younger generation of Malaysian Tamils, who seem apathetic towards their roots and, due to this, have lost their sense of identity and are directionless in the fabric of Malaysian society. He further conveyed that, because of their lack of understanding of themselves, Malaysian Tamils are concerned with a false sense of heritage and history while trying to compete with the other Malaysians in superficial aspects. Sandrasegaran wants this book to be a starting point for Tamils to truly understand Malaysian Tamil history, one that doesn’t drown in the venom of glorification while also fighting against the extremist and xenophobic predicament that Tamils, as well as other non-Malays and non-indigenous people, are merely “pendatangs.” Malaysia as a nation and idea is one that was birthed and materialised through the labour of many communities, the Tamils being one of them. To conceal Malaysian Tamil history is to deny a monumental element of Malaysian history as a whole. Only through a complete and utterly honest understanding of history can the Malaysian Tamils and Malaysian society progress to an equal future.

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook or Telegram for more updates and breaking news.